Paanch (2003)

Director: Anurag Kashyap; Writer: Anurag Kashyap; Producer: Sanjay Routray, Tutu Sharma; Cinematographer: Nataraja Subramanian; Editor: Aarti Bajaj; Cast: Kay Kay Menon, Aditya Srivastava, Joy Fernandes, Vijay Maurya, Tejaswini Kolhapure, Sharat Saxena, Anand Mishra, Mukesh Bhatt, Siddhu, Loveleen Mishra, Suresh Singh, Suhas Joshi, Nimit, Praveen Patel, Vijay Raj, Pankaj Saraswat, Tutu Sharma

Duration: 02:39:50; Aspect Ratio: 2.341:1; Hue: 198.864; Saturation: 0.106; Lightness: 0.217; Volume: 0.148; Cuts per Minute: 19.882; Words per Minute: 53.441

Summary: Ranjani Mazumdar writes:

Paanch narrates the story of a rock band called “The Parasites”, who live in a Bombay chawl. One day a man who claims to represent a music company tempts the band. At the same timet the band needs money to cut their first CD. The group decides to stage a fake kidnapping where Nikhil, the wealthiest among the group, is ‘kidnapped’ with his permission to extract money from the father. This simple plan turns into a nightmare, soon striking the heart of the band. The father informs the police and trouble follows. Luke, the domineering head of the band murders Nikhil in a fit of temper. As one thing leads to another, the band members lose control leading to four other murders. Violence, betrayal, death and destruction unravel in a film that enters heterotopic architectural and psychological spaces of Bombay. The band is made up of Joy (Joy Fernandes), Pondy (Vihay L. Maurya), Murgi (Aditya Srivastava), Shivli (Tejaswini Kolhapure) and Luke (played by Kay Kay Menon).

In an interview to the Financial Express a few years ago, Kashyap recalled his vision behind Paanch “Around 1995, I used to spend a lot of time with Imtiaz Ali at St Xavier’s College, Mumbai. A band called Greek (now Pralay) performed regularly in the college circuit and I used to hang out with them like a groupie. I wanted to make a film on a rock band and that was the genesis of Paanch. But the idea didn’t work out. I tried remodeling the concept around a brass band because I was very impressed with a song in the 1988 film Om-Dar-Ba-Dar. But I could never get beyond a point. (I went back to the idea in Dev.D for the song Emotional Atyachaar.) Then, when I started working with (television director) Shivam Nair, I came across many criminal files, including the Joshi-Abhyankar serial killings (on which Paanch was based). The key member of that gang, Rajendra Jakkal, was very similar to Luke, the leader of the rock band in my film. He was a prodigy; he worked, topped college and also had very strong views on crime. He was the alpha male. In 1998, I decided to marry the two stories”.

http://archive.financialexpress.com/news/-the-myth-of-paanch-is-bigger-than-the-film-/847510/2

On the Abhyankar murders:

http://murderpedia.org/male.J/j/jakkal-rajendra.htm4 friends (Luke, Murgi, Joy and Pondy) wasted by youth and self destruction play together in a band along with a fifth female member (Shiuli). Luke the lead singer and self-imposed leader of the pack ensures his dominance in the group by providing accommodation, drugs and food for his wasted and broke friends. Pondy is fascinated by Shiuli who sleeps with rich guys for money. The movie revolves around a kidnapping plot gone wrong, in which the 4 male band members plan to kidnap another friend Nikhil. Nikhil is part of the plot and agrees to get himself kidnapped to extract money out of his rich but miser father. In the process excess of drugs and uncontrolled anger leads to the murder of Nikhil by Luke. Luke blackmails all others and ensures that nobody leaves or confides into the cops. Meanwhile Shiuli also gets entangled into the plot. The money hungry youngsters then go on to kill the father of Nikhil and a cop (Sharat Saxena) investigating the murder. The plot thickens with a set of betrayal and counter-betrayal leading to an interesting end.

censor certificate

Paanch narrates the story of a rock band called “The Parasites”, who live in a Bombay chawl. One day a man who claims to represent a music company tempts the band. At the same time the band needs money to cut their first CD. The group decides to stage a fake kidnapping where Nikhil, the wealthiest among the group, is ‘kidnapped’ with his permission to extract money from the father. This simple plan turns into a nightmare, soon striking the heart of the band. The father informs the police and trouble follows. Luke, the domineering head of the band murders Nikhil in a fit of temper. As one thing leads to another, the band members lose control leading to four other murders. Violence, betrayal, death and destruction unravel in a film that enters heterotopic architectural and psychological spaces of Bombay. The band is made up of Joy (Joy Fernandes), Pondy (Vihay L. Maurya), Murgi (Aditya Srivastava), Shivli (Tejaswini Kolhapure) and Luke (played by Kay Kay Menon).

In an interview to the Financial Express a few years ago, Kashyap recalled his vision behind Paanch “Around 1995, I used to spend a lot of time with Imtiaz Ali at St Xavier’s College, Mumbai. A band called Greek (now Pralay) performed regularly in the college circuit and I used to hang out with them like a groupie. I wanted to make a film on a rock band and that was the genesis of Paanch. But the idea didn’t work out. I tried remodeling the concept around a brass band because I was very impressed with a song in the 1988 film Om-Dar-Ba-Dar. But I could never get beyond a point. (I went back to the idea in Dev.D for the song Emotional Atyachaar.) Then, when I started working with (television director) Shivam Nair, I came across many criminal files, including the Joshi-Abhyankar serial killings (on which Paanch was based). The key member of that gang, Rajendra Jakkal, was very similar to Luke, the leader of the rock band in my film. He was a prodigy; he worked, topped college and also had very strong views on crime. He was the alpha male. In 1998, I decided to marry the two stories”.

http://archive.financialexpress.com/news/-the-myth-of-paanch-is-bigger-than-the-film-/847510/2

On the Abhyankar murders:

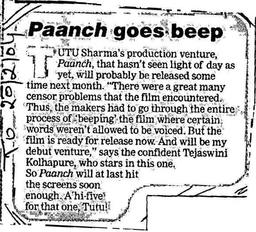

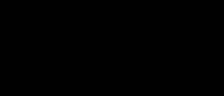

http://murderpedia.org/male.J/j/jakkal-rajendra.htmPaanch was slated for a release in 2001 but soon got embroiled in a censorship battle which finally concluded with some beeps in the soundtrack, a few cuts, and a disclaimer at the beginning of the film. The certificate here is dated 2002 even as the film was scheduled for a release in 2001. The censor certificate displays the “A” sign which the filmmaker had opted for right at the beginning. But the screening committee was not happy with just an A certificate, they wanted some radical restructuring. The disclaimer here on the “nature of evil” and the waywardness of urban youth was introduced in response to the Censor’s attack on the film’s presentation of extreme violence and for its inability to evoke a moral centre in the narrative. By 2001, Kashyap had acquired some recognition for his scripting of Satya (1998). When Paanch became controversial, he did several interviews to express his anger at what he felt was highly unjust.

Introduction Quote: Paanch

William Mazzarella has shown how “aesthetic judgment and cultural grounding” have remained the foundational basis for censorship in India. “Taken together they defined censorship as an activity that must at once be open to cosmopolitan creative provocation and modulated by the moral order of an imagined community. This was the self image of Indian censorship after the 1960s. But things were not always thus” (Censorium: Cinema and the Open Edge of Mass Publicity, Duke UP, 2013, pg 81-82). The debate around Paanch clearly stretched the self image of the CBFC (Central Board of Film Certification) in India. Paanch was made in the midst of the “global avalanche of images” that marked the long 1990s. At one level, the film boasted of an internationally recognizable iconography (associated with the aesthetics of film noir) while at another it tore apart themes of friendship, romance and the family so central to the ‘imagined community’ in whose name regulations had been traditionally imposed. This was a film that seemed to stretch the benchmark of violence and ‘family values’ to create its own form. After some negotiations Kashyap finally came round to accepting a few cuts and some disclaimers. These were intended to position the film as a “lesson in morality”.

Paanch was finally ready for a release with a certificate dated 2002. But now a new problem had cropped up. The financiers decided to block the release because of a dispute with the producer, Tutu Sharma. In public memory, there has been a slippage in the way the film’s marginality is positioned. Most believe the film was not released because of the CBFC even as they finally cleared the film with the cuts. The real reason the film was not released is not as well known. While the promotional trailer of the film was aired on television, till date the film has not had an official theatrical release. It is this unreleased status that has in many ways provided Paanch with an enduring cult afterlife.

In his work on architecture and the modern metropolis, Anthony Vidler conjures a world where subjects are engulfed by spatial systems that are beyond their control. For Vidler it is imperative that we focus on the psychopathology of space to elaborate on the links between architectural forms and the experiences of fear, estrangement, anxiety, neuroses and many other phobias. Space in this formulation is not a passive container of bodies and objects but a site of dynamic interactions. While this line of thinking has been around since the 1940s, Vidler moved the discussion of pathology specifically to the metropolitan experience. This is the construction of warped space, a template through which we can understand the alienation of modern subjects. Warped space for Vidler is not just an externalization of a subject’s interiority but an active player in the construction of inner lives. Warped space is the template through which we can trace the turmoil’s of the modern world (Warped Space: Art, Architecture and Anxiety in Modern Culture, MIT Press, 2001). In spatial warping, photography, film, and digital technologies become active players in the imagination of space. Vidlers formulation resonates with the spatial design of Paanch. The collaboration between Paanch’s production designer, Wasiq Khan and Anurag Kashyap resulted in a series of warped urban spaces. A critic said of the film “In Paanch the city is a merciless adversary that pulverizes every good quality in the man on the street” (Jha: August: 2001).

opening

Paanch opens with images of Bombay stylized through strobe like shots. Edited to the rhythm of music, the sequence conveys energy, diversity of spaces, a sense of the crowd and an air of decrepit gloom. We move between stillness and movement and the disconcerting sound track only adds to the anticipation of a pathological world. But rather than focus on particular characters, the opening credits establish the city of Bombay as the main protagonist. The range of sites include iconic markers of the city along with several unidentifiable interiors. This is very explicitly an architectural language that foregrounds the combined effect of film, photography, architecture and music in the warping of modern space. Many of the images in the opening sequences were shot with a still camera, and movement was introduced through frame by frame editing. (interview with me!)

The opening credit sequence is also a clear citation and acknowledgement of international film influences. Not only did the title of the film resonate with David Fincher’s Seven, even the tone of the music and the stylized editing bore a clear resemblance. While Fincher’s credit sequence showcased a forensic imagination, in Paanch we see images of the city. Both films signal a sense of foreboding in the opening and both deal with warped spaces.

http://kino-obscura.com/post/1166681472/great-scenes-seven-david-fincher-1995-one-manFincher’s opening was a citation to the American avant-garde filmmaker, Stan Brackage’s 1963 film, Mothlight.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yt3nDgnC7M8 Flickers and scratches seem to be common to all three films revealing a clear desire for distortion. The circuit of influences here is also a mark of the cinephilic surge that had emerged so strongly in the context of the digital explosion at that time. In many ways Kashyap’s cinematic foundations emerged through this particular moment of global culture, digital explosion and DVD piracy. He poured all that he was drawn to into his debut feature. Kashyap’s home at this time was crowded with books and DVDs on film noir. He had not been outside the country, did not own a passport but had the largest collection of books and DVDs on film noir. In a discussion at a film appreciation session in Delhi, in 2003, Kashyap spoke about his love for graphic novels and noir, both of which appeared familiar to him when he first discovered the forms.

On the contrary, the opening

Pondy’s first encounter with Luke is staged at the site of the Watson Hotel in South Mumbai, now known as Esplanade Mansions. The hotel is India’s oldest cast iron building, well known for its elite clientele under the British. In popular memory however, the hotel is best known for the Lumiere screenings held in July 1896. The history of motion pictures in India and the history of colonial rule coincided in the architectural space of the hotel. In 1960, the hotel shut down and subsequently became a place for tailors, photocopiers etc. At the end of the twentieth century, standing as a ruinous building marked by the vestiges of time, Watson hotel appears almost like an archeological site, offering us entry to a maze of connections. A building of such significance and history now stands decrepit and out of joint with the time of globalization. There is nothing unique about the building anymore, except for a fading legacy. When Pondy asks Luke when the building came into existence, Luke’s reply is a counter question “are you going to freeze that era into an ice cream”? This conversation is staged against a walk up the stairs. Kashyap’s use of the Watson hotel as the entry to Luke’s apartment is clever. It reveals the crevices of the city through its most significant buildings. The passage of time only allows us to reflect on this constant state of flux that all cities experience. Pondy looks up when he asks Luke about the hotels history. They go up the stairs and then he looks down from the balcony to ask what lies down in the quadrangle. While Watson hotel may not be clear to all spectators, the buildings sense of pastness is. Architectural space operates here as a witness to the past, future and present of Bombay. In globalized Bombay with its rapid transformations, Watson hotel stands as the trace of a time out of joint with the present. Its many memories also imaginatively bring about a collision between cinematic history and the present. Pondy and Luke’s volatile relationship is introduced through this spatial language.

Beep

'Chutiya' is deleted here

By the end of the 1990s MTV and Channel V were both very popular on television and known for their broadcast of a combination of Indian and International pop music. Music videos were the rage at this time in India with several countdown shows playing the most recent hit songs. Yet the choice of music in Paanch is a 1960s and 70s style hard rock associated primarily with the Doors. The specter of the groups lead singer and writer, Jim Morrison, is presented through his recurring circulation in the narrative as a photo, a sticker, a wall poster, and poetry on the wall. As a group trying to make it big in the music industry, the musical scores played by the band appear from another time. Even the style of the stage performances appear out of place. Instead of the rapid editing and dancing associated with music videos of that time, we have a hazy form reminiscent of the post Woodstock generation. This is a clear case of time out of joint. This could not have been accidental since it is made so spectacularly visible, especially in the way the rehearsal space is crafted. Paanch displays an anachronistic drive, a refusal to inhabit the time of the present. This is established primarily through the development of its musical universe. The narrative does not seek accuracy in representation. Instead we see a canvas of characters and their relationship with music unmarked by contemporary trends. Wrenching their world away from the temporal succession of chronological time, Kashyap uses music from another era to create a landscape of time out of joint. This could not have been accidental since it is made so spectacularly visible, especially in the way the rehearsal space is crafted.

The warehouse that belongs to Nikhil’s father is where the band rehearses. In contrast to the red hue of the apartment walls, the warehouse was designed with a flat blue cast. Wasiq Khan’s production design made the window less walls of the warehouse into a different kind of surface from the home. Packing cases can be seen against the walls along with a giant sketch of Morrison and a caption of Abba. It is in this space that we see the band get stoned, sing, make merry and fight. Walls tend to reflect fear as well as provide a sense of security. Inside the four walls of the warehouse the group comes into its own. They can sing the songs they want to and shield themselves from the powerful soundscape of music associated with globalization. Music literally hits against the walls and is expressively captured by Natrajan’s swaying camera. The walls provide the dividing line between an outside and inside. In this space, time stands still for the band. This protective shield will however disappear when Luke brutally murders Nikhil.

Song: Pakaa mat

Song: Akhiyaan chipki

Song: Mai Khuda...

Sar jhuka, khuda hun mai

Beep

'Chutiya' is deleted here

Beep

'Chutiye' is deleted here

Beep

'Chutiya' has been deleted here

Beep

Indecipherable beep

Song: Yeh kaisa hai shehar

'Chutiya' is muted instead of being beeped

Muted

The walls in Paanch are ornamentalized through desecration. This is particularly true for Luke whose room is hidden from all the others in the band as well as the spectators, revealed much later in the film. Wasiq Khan created a “red room” of painted walls, etchings, poetry, cartoons, and photos. The shooting of this interior was carefully planned to ensure the walls could express along with the characters. The walls in fact are discussed several times in the film. As an interior this space was significantly different from Farhan Akhtar’s Dil Chahata Hai (2001).

Kashyap himself has stated how Paanch tells us a story that is radically different from the world of Dil Chahata Hai which presents the experiences of three young friends from privileged backgrounds who live a lifestyle surrounded by architectural landscapes that belong in a design catalogue. All three characters in DCH have cars, mobiles, flat screen TVs, fashionable clothes and high-end computers. The sets are mounted in the film to provide consistency to the characters individual personalities. The interiors are shot not in the classic panoramic style of Hindi Cinema, but through angular shots that convey an almost modernist and minimalist framing.(Bombay Cinema: An Archive of the City) If DCH deployed an architectural landscape identified with an aspirational culture, Paanch generated space as a trace of and witness to the psychic registers of being out of joint with time.

Inspector Deshpande’s investigation of Nikhil’s disappearance brings him to the apartment. Deshpande’s search takes him to Luke’s room and becomes an occasion to highlight the walls, the objects, old magazines and the overall layout of the place. The search reveals a maze of artifacts, objects of everyday use and violence. Luke’s room operates like a secret chamber, hiding perhaps the key to his personality. Yet everything Luke does defies easy categorization. There is no easy explanation for his behavior nor do we have access to a suppressed past. Luke is what he is, and emerges for the spectators through his performative energy. As a pivotal character of the film, Luke embodies the contingency of violence without a past or future. Kashyap was interested in this combination of a murderous rage, arrogant stance and the ability to psychologically control his friends. In all his later films (No Smoking, Ugly, Gangs of Wasseypur, Gulal), Kashyap has displayed a penchant for such characters with absolutely no desire for sociological explanation. Indeed his interviews have always alluded to this interest in the subterranean, the world just below the surface.

The use of the bathroom as a recurring space in the narrative is very deliberate. It is the one space in the claustrophobic apartment where a person can be alone. Therefore more than just a backdrop its use in the film is deliberate. When Pondy breaks down after he inadvertently kills the constable in the apartment, he is unable to deal with this reality. He locks himself in the bathroom in despair and tries to unsuccessfully kill himself with a blade. We hear the sound of water in the sink, dripping incessantly. The aural capture of this repetitive sound signals both the ruinous decrepit state of the building as well as the passage of time. This daily life ‘noise’ is enhanced to envelope the space of the bathroom where Pondy crouches in one corner. Michel Chion has referred to “reduced listening” as the perception of sound that comes to us in our daily lives, unprocessed and cluttered. This is noise that requires recording in order to hear and process it. ('The Three Listening Modes', in Jonathan Sterne ed. The Sound Studies Reader, London and New York: Routledge, 2012, pp 48-53). The sonic trace of reduced listening can open up new horizons and questions. In the bathroom sequence, sound is absolutely critical to the production of warped space.

Song: Tamas

Song: Mai Khuda (female)

The most striking element in the film was the representation of Shiuly. As the femme fatale she does not get punished at the end of the narrative (like in most of classic Hollywood film noir) but journeys through the film with her sexualized performance, finally emerging as the victorious figure. This was a rare feat for Hindi cinema, to have a woman enter the space of masculinity with confidence and then participate in an intriguing plot to get all the money. As a singer in the band, she is independent, making her own decisions. Her final collaboration with the policeman implicates the forces of legality as an extension of the crime world. Within the classic structure of Hindi cinema, Paanch established many feats as it broke the narrative codes of what was socially acceptable at that time.

Paanch offered us a journey into areas of urban life not addressed through given generic structures. It flouted certain conventions of Hindi cinema to create an expressionistic tapestry on urban life. This was neither a perfect portrait, nor a falsification of urban life. Paanch was a film that struggled to articulate something that had not yet been captured within the Bombay film industry. It did not offer us a causal narrative, nor did it suggest a way out of the depraved form of urban living that affects the lives of the films protagonists. What made Paanch interesting was its desire to flout norms and taboos. The victory of the femme fatale in a cinematic practice that has always morally coded women is the most striking feature of the film.

The word cult is usually used to identify films for their ability to display a critical engagement with taboo, transgression, perversity or decadence. These films draw attention to censorship regimes within which transgression operates as a window to both the paradigm of the mainstream and to the language of a cinema that is perceived as different. Excess and controversy shadow cult films. It is a value produced by spectators, markets and festivals. Manny Farber has defined cult as a form of “Termite Art” primarily because these films do not claim any social vision. Cult films find an audience even if the tastes of the majority run counter to them. Films that don’t circulate in the mainstream have a greater chance at becoming cult since the fans keep the memory of these films alive. As has been argued, cult makes its presence in many guises, as schlock, as marginal cinema, as passionate indulgence, as fad, as fashion, and as the spirit of subversion. Cult is also associated with underground cinema and the cultures of cinephilia. Cult generates a sub cultural network of spectators who provide certain films with their complex afterlives. ('Cult Cinema: A Critical Symposium', Cineaste v 34, n 1 (Winter 2008), pp 43-50; Please see Ishani Dey’s Unpublished M.Phil dissertation for broader account of Anurag Kashyap’s status as auteur and entrepreneur [From Bootleg To The Big League,Negotiating Bollywood: Anurag Kashyap the Auteur Entrepreneur, School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, 2014] Dey mobilizes a discussion of Kashyap’s cult following via censorship debates, festivals, and a changed aesthetic context with the movement of transnational capital )

For all these reasons we can now clearly identify Paanch as a cult film for the way it acquired a controversial life since its inception. For Kashyap, the myth of Paanch remains bigger than the film, it was the forbidden film that some saw, others didn’t but there was much conversation generated around it. (reference). Despite its narrative flaws, Paanch generated unusual spatial passages and remains a key nodal point of departure for many films identified with a new generation attempting to move away from standard fare. There is now something that we can easily refer to as the “Paanch effect”. Elements of this unreleased film have found their way into other films. In Kashyap’s own Ugly (2013), we see thematic and stylistic similarities. Like Paanch, a kidnapping story is placed at the centre of Ugly to showcase deeply troubled psychological worlds. In Bijoy Nambiar’s Shaitan (2011), we see a similar breakdown of friendship when they find themselves on the wrong side of the law. These examples draw our attention to the way cult films leave their signature mark on the body of other films. The cult afterlife of a film is a discourse that is available in casual conversations, memories, newspaper and magazine articles, interviews with directors and actors, circulating video clips, and fan statements. The stylistic and thematic carryover to other films also enables the discussion to continue in relation to the original source. We have to see how many productions in the future will carry this mark of an unreleased film.

http://www.firstpost.com/bollywood/movie-review-ugly-is-anurag-kashyaps-best-film-since-black-friday-2013015.htmlhttp://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/entertainment/hindi/bollywood/news/Is-Shaitan-a-revamped-version-of-Kashyaps-Paanch/articleshow/8662149.cmsThe YouTube version of Paanch was uploaded in 2010 and has also been crucial in the constant production of opinions, nostalgia, memories, and criticisms. YouTube is now the epitome of digital culture because it promises opportunities for both marketing and for the odd post by “you” which could change history (Pelle Snickars and Patrick Vonderau, 2009, 11). The online leak of a preview copy with all the beeps in place and the word “preview” placed in the corner of the frame has made this early work of Kashyap visible to a world that had never seen it. This presence both adds to and demystifies the myth attached to the film. Now that Paanch is traversing digital territory, its cult life faces new challenges as it negotiates the complicated relationship between technology, memory and community (For a discussion of You Tube as a platform see Pelle Snickars Patrick Vonderau The You Tube Reader National Library of Sweden, P.O. Box 5039, 10241 Stockholm, Sweden, 2009)

Indiancine.ma requires JavaScript.