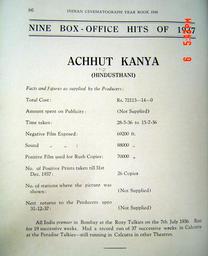

Achhut Kanya (1936)

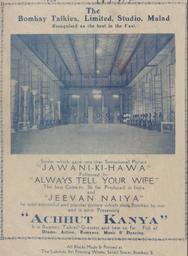

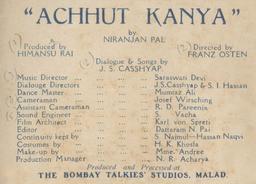

Director: Franz Osten; Writer: Niranjan Pal; Producer: Himanshu Rai; Cinematographer: Josef Wirsching; Editor: D.N. Pai; Cast: Devika Rani, Ashok Kumar, Monorama, Pramila, Kamta Prasad, Kusum Kumari, Anwari, P.F. Pithawala, Kishori Lal, Ishrat, N.M. Joshi, Khosla, Mumtaz Ali, Sunita Devi, Najam Naqvi

Duration: 02:15:58; Aspect Ratio: 1.333:1; Lightness: 0.318; Volume: 0.195; Cuts per Minute: 4.457; Words per Minute: 55.560

Summary: A circular story told in flashback, in which eternal repetition is only interrupted with death in the form of the relentlessly linear railway engine. The film opens at a railway crossing where a man is about to kill his wife when the narrative spins into the past via a song. The central stroy is of the unhappy love affair between Kasturi (Devika Rani), the Harijan (Untouchable) daughter of the railway levelcrossing guard Dukhia (Rasad), and Pratap (Kumar), the Brahmin son of the grocer Mohan (Pithawala). At first rumour and mob violence are deployed to lethal effect in order to maintain a 'traditional', opressive morality. Later, when the main protagonists are about to conform to marry selected partners, rumour and maliciousness again intervene to trigger renewed violence until the on-rushing train of fate stops the strife. Enhanced by Wirsching's contrasted imagery, the plot suggests that both conformity and nonconformity are equally impossible options, the latter being punished by society, the former unable to suppress what it oppresses. The standard formal conflict between circular/traditional time and linear/modernising time is undercut by the suggestion that social-ethical change is as untenable as social stasis. Even fate, associated with the archetypal symbol of modernity and progress, is denied its ultimate victory: the spirit of the defeated lingers, haunting the crossroads, testifying to the ineradicability of desire. The film's narrative structure and its eruptions into visual stylisation can be seen as a more intelligently complex way of addressing the encounter between Indian and European notions of history that many an attempt to take East-West differences as an explicit theme. With this film, Bombay Talkies also invented its Anglicised fantasy of an Indian village which became a studio stereotype (

Janmabhoomi, 1936;

Durga and

Kangan, both 1939;

Bandhan, 1940), resisting the generic shift in the formula initiated by S. Mukherjee and Amiya Chakrabarty. Hero Ashok Kumar later said that he felt his acting in this film to be 'babyish'.

World Distributers Super Film Circuit Bombay

Fade In

Titles

Bombay Talkies Ltd

Devika Rani

Devika Rani

in Achhut Kanya

Achhut Kannya

Niranjan Pal's credit is positioned before Himansu Rai and Franz Osten, indicating his importance in the BT 'family' and his centrality in the planning of its films. The film was based on a story Pal had written in England, titled Level Crossing.

In his memoirs, Pal mentions that this story was about "the ill-fated love of a Brahmin boy for a scheduled caste girl. As no equivalent film title could be found for Level Crossing, Himansu agreed to Achhut Kanya much to my disgust. The film was shot, edited and readied for release in just eight weeks and turned out to be an outstanding success. The Congress leader, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, specially came to Bombay to see the film at the Roxy cinema and gave it unstinted praise. Devika was hailed as the Queen of the Indian screen, though Ashok Kumar was to wait for a few years before having a similar distinction.” (

Such is Life), ed. Lalit Mohan Joshi and Kusum Joshi, p. 240).

Produced By Himansu Rai

Directed by Franz Osfen

Savak Vacha, the sound recordist credited here, soon became a key member of the BT core group and was part of the breakaway unit that formed Filmistan. Around 1945, after the departure of Devika Rani, Ashok Kumar and Vacha returned to revive Bombay Talkies. They were responsible for a new wave of BT hits, most notably Mahal (1949), which was shot by Josef Wirsching who was free to work again now that the war was over.

It should come as no surprise that very little is known about Vacha's early life, film training, and career. As usual, there are important clues. JBH Wadia, in his unpublished memoirs titled Those Were the Days, recalls that Vacha had freshly returned from Paris in the early 1930s and had joined Wadia Movietone as their Assistant Sound Recordist.:

"I was already impressed with his abilities. A brain wave came to me. So one fine evening I saw him in the recording room and asked him if he wanted to be the recordist of Bagh-E-Misr [1934]. 'I would simply love to' he said. 'But Wadia Seth, I am as yet an assistant only.' I put my hand on his shoulder and said, 'Well, I’m giving you the opportunity to be one.' And that is how Savak Vacha had his first assignment as recordist of Bagh-E-Misr. Of course, he soon became a competent recordist and in the course of time became the partner of Ashok Kumar when the duo took over Bombay Talkies Studio. He produced a prestigious film Yahudi with Dilip Kumar and Madhubala, which is being screen even today." (c 1980. Many thanks to Rosie Thomas for this information).

So we learn that Vacha had spent time in Paris and probably studied Sound Recording in the French film industry. This nugget adds up with a conversation I had with Wolfgang Peter Wirsching, son of Josef Wirsching, in 2013. We were looking at some production stills from Jawani ki Hawa (1936) and I noticed a pretty, and young European woman with Devika Rani and Charlotte Wirsching. WP Wirsching said she was Vacha's wife, a French woman who also served as the BT make-up artiste in their early films! Interestingly, 'Madame Andree' as she was known, is absent in these opening credits but present in the song booklet credits:

car

gate

level crossing

AUD Class 1

Very dramatic opening in which plot information is provided via cryptic dialogue and suggestive images. Mr and Mrs Premchand, a modern affluent couple, are stuck at a level crossing. The revolver in the glove compartment, the low key lighting that highlights the wife's apprehension, the gatekeeper's mysterious words, are all stylized elements from the internationally circulating suspense-thriller genre. An emphatically urban cinematic mode, the juxtaposition we see here of psychology and crime, became the bedrock of film noir (via German Expressionism).

ghost

guard

level crossing

Bribe

car

couple

gun

revolver

shrine

song

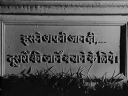

Song: Hari base sakal sansaaraa

हरी बसे सकल सनसारा

moon

ghost

spirit

The appearance of a 'Spirit' strikes an uncanny note in this otherwise recognizably modern murder-adultery plot. Achhut Kanya is Bombay Talkies' first attempt to move away from urban socials and into a rural setting. This dissonant intrusion of the spectral fakir, an intrusion of the supernatural into the secular, emblematizes BT's struggle to fuse the international and the local. It should therefore be seen as part of the studio's project to combine its European training, its cosmopolitan influences, with an idea of the Indian 'authentic'.

Saraswati Devi's song compositions exemplify these efforts as she blends her classical orientation with eclectic instrumentation and simple tunes. This devotional song was sung by MG Basarkar and composed in Raag Malkosh-Tritaal.

ghost

spirit

epithaph

Children

Bird

Free

Train Flags

Snake

Snake

Snakebite

Caste

Couple

Ghost

Spirit

Anglicized

Teenagers

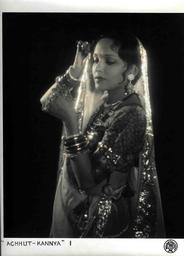

Devika Rani's exclamation "Pratap!" is unmistakably Anglicized in its accent. A reviewer (most likely the Goan firebrand, Clare Mendonca) had this to say of her role as Kasturi: "No village girl ever had such eyebrows as Devika Rani and her coiffeur and her costume towards the end are far too elaborate and rich to be in character. But these slight flaws can be easily forgiven in considering a portrayal that is perfect in its histrionic merit and sympathetic understanding, a real gem of pure acting which places her at the head of India's screen stars, which Garbo herself could hardly surpass." (Times of India, Jul 24, 1936).

Bullock Cart

Caste

There is more to the caste-based discrimination that these friends face: Babulal Vaid, the village medicine man, is trying to sabotage the grocer's quinine sales. Caste prejudice is used to further economic interests, thus exposing one of the historical engines of caste violence.

The parallel message about modern medicine's superiority to 'fake' local remedies, is repeated in Janmabhoomi (1936). Janmabhoomi is an explicitly reformist, even agitational film, with the central message of 'sewa' or service of the motherland. This educational song by Devika Rani and Chandraprabha captures the film's tone:

"Mata ne, hai janam diya jeene ke liye

Nahi rogon se marne ke liye.

Amreeka Jaapaan, Europe Englistaan

Sab bachey hue rogon se

Hai desh hamaara hara-bhara

Phir bhi har praani mara-mara."

This song can be roughly translated thus:

"The Mother goddess gave us life so we could live/

Not so we died of disease./

America, Japan, Europe, and England/

Are all protected from sickness./

Our nation is green and fertile/

But its people are diseased and dying." O

Doctor

Quack

doctor

Bullock Cart

Romance

Song

Teenage

Song: Khet ki muli baag ko aam

खेत की मूली बाग को आम

Flagman

Train

Flagman

Bullock cart

Bullock Cart

Feast

Song

Arranged marrige

Arranged Marrige

Sung by: Miss Kusum Kumari and others

Ragini Mishr-Kaharva

The song booklet calls this ‘a rustic song’ (grameen geet). Songs and dialogues are written in a Hindi dialect that appears to be khariboli. Eminent Hindi scholar, Harish Trivedi uses the dialogue in this film to argue that ever since Achhut Kanya, "films set in villages" used a "kind of constructed Hindi dialect" in order to "authenticate all representations of village life in Hindi cinema, right down to Lagaan (2001). While I agree that the dialect form is being used to impart a sense of realistic everydayness and authenticity, to generalize about all village film dialogue ever after is surely a bit misplaced.

"Dheere bahu nadiya, dheere bahu, hum utarahin paar

Kaahe ki tori nayya re, aur kaahe ki patwaar

Kaun tora nayya khivayyare kaun utarhi paar

Dheere bahu

Dharm ki mori nayya re, sat ki patvaar

Saiyyan mora nayya khivayya re, hum utarhin paar

Dheere bahu"

churner

Apothecary

Doctor

AUD Class 2

Vignettes of village life: social relations & hierarchies, idiomatic phrases, superstition, and rumor.

Superstion

Oil

Oil

doctor

Winnower

Bullock cart

Bullock Cart

The slow enumeration of of Kasturi & Pratap's caste transgressions begins.

This song became an all-India hit and was on the lips of every college student of the time. It was composed by Saraswati Devi (nee Khorshed Homji) who had to work out very simple tunes, with nursery rhyme rhythms for Ashok Kumar and Devika Rani, as they were both completely raw and untrained as singers. This was an era before the playback system came in and actors had to sing their own songs while shooting.

As Roshmila Bhattacharya describes it, “The songs were sung on the sets by the actors themselves. Later, shorter versions that could be included on a 78 rpm record, were recorded in the HMV studio. For these three-minute numbers, all the musicians and the singer-actors had to troop into the studio, usually late at night when traffic was thin and the danger of being interrupted by honking vehicles and nosy passer-bys was diminished somewhat.” BT could manage the sound question by shooting on its own, secluded studio premises.

Saraswati Devi was one of India's very first female film music directors, an honour she shares with the inimitable Jaddan Bai, who is remembered today as the mother of Nargis. Jaddan Bai's film Talash-e-Haq was released in September 1935, just a few months before Achhut Kanya. (See Ashok Da. Ranade, Hindi Film Song: Music Beyond Boundaries, 2006). On the other hand, recent popular sources suggest that Ishrat Sultana, also known as Bibbo, might have been the first female music director with the 1934 film Adil-e-Jehangir.

The popularity of Achhut Kanya in general, and this song in particular led to several criticisms and parodies, including this famous song sequence from V Shantaram's Aadmi (1939):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JnuwbWxX2kQFor a detailed discussion of this parody as a "submerged review" of Achhut Kanya and Bombay Talkies's production style, see Neepa Majumdar (2009), Wanted Cultured Ladies Only! Female Stardom and Cinema in India, 1930s-1950s, pp. 86-90.

doctor

Kalyani (Kusum Kumari) meets a prospective bride for her son. This serves as an occasion to state an anti-dowry position.

AUD Class 3

This is a crucial scene as it lays out the main tensions in the village that will ultimately lead to tragedy. The scene dissects the way in which economics and petty egotism can be mobilized against an individual. It also suggests that this is a peculiarity of village life, with its proximate relations and informal, community platforms for punitive action.

Another complex scene that keeps the viewer on her feet with its shifting moral centres. It begins with Mohan - established as a positive, charitable character - demanding dowry for Pratap's wedding. His wife, Kalyani - established as a slightly negative character, with her caste prejudice - is staunchly anti-dowry. This confusing role reversal is happily resolved by the end of the scene.

Sung by: Chandraprabha

Ragini Jhanjhoti-Dadra-Kaharva

"Kit gaye ho khevan haar..nayya doobti

'Jo main aisa jaanti..peet kiye dukh hoye

Nagar dhandhora peet-ti..peet na kariyo koi.'

(Meera Bai)

Mohe chhand chale majhdhaar..nayya doobti

Kit gaye…

Bichhad gaye more sang sanghaati

Naav khivayya, jeevan saathi.

Mohe kaun lagaave paar..nayya doobti..kit gaye."

The actress playing the old woman is Manek Homji, rechristened 'Chandraprabha' for her screen debut. The classically-trained Parsi sisters, Manek and Khorshed Homji had a popular musical programme on the Bombay radio during the late 1920s and the early 1930s. They composed and sang their own songs and employed an eclectic selection of instruments from the dilruba to the sitar to the organ.

Here is a newspaper listing for their radio programme, dated September 29, 1930:

When Himansu Rai offered them work at his new studio in 1935, the Parsi community erupted in protest. Ultimately, the two sisters continued with their film careers but under assumed screen names. Khorshed Homji, of course, became Saraswati Devi.

For a detailed discussion of the scandal caused by the Homji sisters, and Khorshed's subsequent career see my essay "Notes on a Scandal: Writing Women's Film History Against an Absent Archive" here:

https://www.academia.edu/5995913/Notes_on_a_Scandal_Writing_Womens_Film_History_Against_an_Absent_Archive

This scene is almost certainly shot in Malad, near the BT studio premises. In the 1930s Malad was not the bustling suburb it is today. Sparsely populated, it has been described by BT technicians as a 'jungle'.

In many ways this sequence is the climactic moment in the film. The caste tensions and petty interpersonal village politics have been gradually building up to this point of eruption. The conservative Vaid (local doctor) is afraid of losing his social status and family job to a mere grocer who distributes free quinine. He leads a gang of villagers to Mohan's house, ostensibly with the aim of repairing the 'imbalance' caused in the Hindu universe by Dukhia's presence.

Such mob anger and escalating violence will surely strike a chord with anyone familiar with caste and religious riots in India today. The Vaid's rousing speech meant to incite the mob, as well as Mohan's grand message of human equality also tragically resonate with current rhetoric on the subject.

Clip for class

This is the sequence that Ravi Vasudevan references in his essay 'Film Studies, New Cultural History, and the Experience of Modernity': on parallel editing.

The train is a constant presence that informs the entire film, even in its absence. It is the source of Dukhia and Kasturi's livelihood, it is the cause for the estranged couple from the frame story to halt and revise their relationship, and ultimately it becomes the engine of destruction. In this scene we get some clues about the script's ambivalence towards the train, and hence to modernity itself. Dukhia tries to stop the train as it can take him to the city and to a 'real' doctor trained in Western medicine. However, it is the train's essential character - its speed - that injures him.

Years later when Apu and Durga wait for their train to arrive, they too look on it with ambivalence - but their ambivalence is distributed into two characters. It is important to note that the train holds no mystery, magic or terror for Dukhia and Kasturi. It is a technology that they interact with on a daily basis and even take for granted. This familiarity makes the betrayal so shocking and uncanny - that this familiar object can become a hostile instrument of violence.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d-JWZDALouI

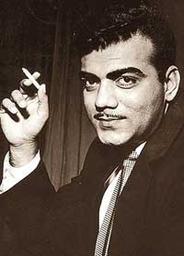

The role of the Railway Officer is played by Sashadhar Mukerji who started his film career as a sound recordist at Bombay Talkies. You see him in a similar walk-on part in BT's first film, Jawani ki Hawa. Mukerji went on to become a powerful producer and headed the BT breakaway group that eventually formed Filmistan Ltd. Mukerji later founded Filmalaya and is responsible for the 1960s sweetheart romances starring his 'discoveries' like Asha Parekh and Sadhana. As Ashok Kumar's brother-in-law he was responsible for introducing the thespian into the film world.

As Neepa Majumdar points out, "Achhut Kanya's critique of the caste system was coupled with a similar critique of traditional forms of medicine, village justice, and moral codes, against which were placed modern medicine (practiced by the grocer) and the impersonal law of the state, enforced by the police who intervened at the end." (Wanted Cultured Ladies Only, pp 86-87).

Kasturi's song of separation. Devika Rani's singing style seems clearly influenced by Rabindra Sangeet's emphasis on drawn out, well-rounded transitions. She was, after all, Tagore's grandniece.

Sung by: Ashok Kumar

Ragini Maand-Kaharva

“Kisse karta moorakh pyaar, pyaar, pyaar,

Tera kaun hai

Jhoote jag ke naatey-rishtey

Jhoothi jag ki preet

Jhootha jag ka milna-julna

Ulti jag ki reet

Nahi meet koi, nahi yaar, yaar, yaar,

Tera kaun hai

Kisse karta moorakh pyaar, pyaar, pyaar,

Tera kaun hai.”

This is a a deliberately simple tune catering to Ashok Kumar's untrained voice. The too-obvious lyrics and repeated rhymes follow the logic of what is now called a 'pop song'.

AUD Class 4

This is quite a bold scene, played out simply, with minimal histrionics. Pratap, now a married man, declares his love for Kasturi and suggests that they elope. Pratap has so far seemed a poorly-sketched, meek boy. His easy acquiescence to the arranged marriage with Meera further reinforced this impression. Now however, in a move quite distant from the Devdas-prototype, Pratap is emboldened to take a very drastic step.

Kasturi is tempted, but remembers the horrible repercussions of their recent caste transgressions. She privileges good sense over emotion and refuses to elope. Pratap makes a fervent prayer to God that was surely meant to be provocative at least, and blasphemous at worst: "Oh God, why didn't you make me an untouchable too?"

Devika Rani's curls, angular penciled eyebrows and lustrous lipcolor are gorgeous and she looks truly luminous, if not a 'realistic' village belle. If ever a concession need be made in the name of cinematic license, it should be made for this scene and 'the face of Devika Rani'.

Sung by: Ashok Kumar

Ragini Mishra Maand-Kaharva

"Peer-peer kya karta re

Tera peer na jaane koye.

Tere dil ki lagi koi kya jaane

Tan peer badi koi kya jaane

Ghayal ki gati ghayal jaane

Aur na jaane koye."

Elaborate and memorable fair sequence, with high production values. Osten and crew manage to create the right mix of chaos and festivity. The huge crowds visible here might have been hired, or more likely simply invited to a controlled fairground set. I have not come across any production notes regarding this scene (or this film) so it's impossible to tell for certain. The sound design, editing, and cinematography are all in complete sync. The sequence's length and 'silence' imply that it was meant as an independent attraction within the film. But this durational aspect, following close on the heels of Pramila's devious scheming, also builds narrative tension.

Sung by: Sunita Devi, Mumtaz Ali & others

Ragini Mishr Pahari-Kaharva Dadra

“Chudi main laaya anmol re, le lo chudiya le lo

Chudiyan kya hain, resham ke lachhe

Kya hai namoone ache ache

Aavo kar lo mol re..le lo chudiyaan le lo

Hai maal mera anmol, nahin nokhon hai nahi tol

Gar lena ho to bol, koi chudiyan le lo mol

Chudi main…

Pehne suhagin, piya rijhaaye

Kunwari pehne, byaah rachaaye

Kya kya lega mol re

Maal mera anmol re, le lo chudiyan le lo

Chudi main…

Gore gore haathon mein kaali-kaali chudiyaan

Yeh kaali chudiyan hain gore-gore haathon par

Ke zulf kharahi bal hai kisi ke gaalon par

Gore-gore haathon mein kaali-kaali chudiyan

Roop hai aala rang nirala

Joban wala man rijhaaye

Chudi main laya…”

Mumtaz Ali was Bombay Talkies' in-house 'Dance Master' and often appeared in special dance items which were mandatory in every film. These dance spectacles were generally staged as diegetically-driven professional performances such as this group dance at the village fair, stage performances (see Basant) or professional dances at weddings and other festivities

(see Jhoola;

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ShoWrsxiexE).

Mumtaz Ali was the father of Mehmood, the legendary comic actor.

More attractions-style fairgroung vignettes are showcased as Kasturi wanders through the mela. We see fire-eaters, a dancing bear, a fortune teller. Tom Gunning's use of the term 'attractions' itself comes from the fairground and circus, via Sergei Eisenstein.

Is this the longest flashback dissolve in Indian cinema?

AUD Class 5

Truly a stunning finale. All the slow tension that was built up in the false gaiety of the fairground is released in this tragic denouement. Bombay Talkies' first film, jawani ki Hawa, was largely set inside a train. That train was hurrying two fugitive lovers to their happy future. That train too witnessed a death, a cold-blooded murder, but it resulted in a resolution of multiple plot conflicts. This time the train separates two lovers who had resolved not to elope, not to become fugitives in the eyes of society, but it nevertheless results in death. Is it the problem of caste that could not be adequately resolved on screen? Or did something change in the BT vision between Jawani ki Hawa and Achhut Kanya?

Kasturi, the pure-hearted dalit girl saves more lives with her tragic story. The anti-untouchability message of the film brought the studio much favor from Congress leaders. This news article attests to the fact:

(Times of India, August 26, 1936)

Indiancine.ma requires JavaScript.