Nirmala (1938)

Director: Franz Osten; Writer: J.S. Casshyap; Producer: Himansu Rai; Cinematographer: Josef Wirsching; Editor: Dattaram Pai; Cast: Devika Rani, Ashok Kumar, Maya Devi, Kamla Prasad, Mumtaz Ali, P.F. Pithawala, M. Nazir, Saroj Borkar, Yusuf Sulehman, P.R. Joshi, Haridas, Y.G. Takle, S. Gulab, Bhim, Vipin Mehta, Nazeer Bedi, Meera, Gulbadan, Balwant Singh, Swarupa, Ehsan, Pratima, Tarabhai Solanki

Duration: 02:03:36; Aspect Ratio: 1.333:1; Lightness: 0.208; Volume: 0.157; Cuts per Minute: 5.517; Words per Minute: 60.356

Summary: Nirmala (Devika Rani) is a modern girl - young, beautiful, dressed in the latest fashions, attends college, and is even the only female in an all-male class. She doesn't take second place to the men, besting all but one in the annual exams. She tied with Ramdas (Ashok Kumar). But, at the same time she is tied to the age-old culture, traditions and religion. She yearns for a husband and for motherhood. And this conflict forms the crux of the story.

The Indiancine.ma Khazana

Production Logos

I would be grateful for any information on this writer, 'Basudev'.

A young man from Punjab, R.D. Pareenja joined Bombay Talkies in it’s earliest days and was an assistant to Josef Wirsching in the cinematography department. During the Second World War, the German technicians at BT were interned in camps for enemy aliens and Pareenja became the chief cameraperson. He shot Bandhan (1940), Azad (1940), Naya Sansar (1941), and Kismet (1943) during the war. Sometime around the BT split and the creation of Filmistan, Pareenja started his own film company, New Bombay Theatres. Here he directed Sona Chandi (1946), Sohni Mahiwal (1946), Tara (1949), and Bholi (1949). From pre-production reports in 1952, it appears that Pareenja was slated to direct Filmistan’s pirate adventure Samrat but it was finally completed by Najam Naqvi in 1954. It is possible that New Bombay Theatres did not manage to keep its head above the water and in the late 1950s we see Pareenja return to cinematography with Hamara Watan (Jayant Desai, 1956) and Samunder (Prem Nath, 1957).

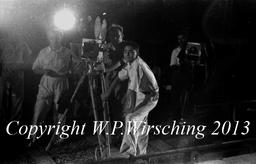

Here is a rare photograph from the sets of a BT film, provided by Georg Wirsching. We see Josef Wirsching behind the camera, flanked by Franz Osten to the left and RD Pareenja to the right.

BT was one of the few film companies at the time that credited the 'dialogue director'. Dialogue directors were essential for instructing actors on pronunciation, even delivery. Not only was Hindi-Hindustani an unfamiliar tongue for the many Bengali and Marathi-speaking actors at BT, but Franz Osten himself spoke no Hindi-Urdu. J.S. Casshyap was an actor as well as writer and thus perfect for this additional production role.

This opening shot is quite striking in its use of a mobile camera and off-screen sound. The dim lighting, the lullaby in the background, and the slow dolly reveal of an empty room strewn with children's toys create an uncanny mood. It is narratologically symbolic that the film begins with an empty children's room as this is the central anxiety that drives the film.

This lullaby was written by JS Casshyap who has been specifically credited as the 'Shabdkar' for this one song in the booklet. Saraswati Devi nee Khorshed Homji composed it in Raga Jay Jaywanti.

The child actor is a girl named Gulbadan. A pre-release publicity article in the Times of India said: "The picture, we understand, has a special attraction in the Indian screen world’s newest discovery, Gulbadan, who portrays the heroine as a child. Gulbadan is just four, but she sings and acts like any veteran." (March 4, 1938).

This sequence, between the mother's lullaby and the daughter's own imitation of it, features about 1'40" of silence on the sound track - nothing except for room noise and mic static. The slightly eerie tone of this sequence thus continues.

The set design, costumes, and props have been carefully planned in these opening scenes to indicate the upper class stature and lifetstyle of this family. Saroj Borkar is outfitted in fashionable georgettes and silks, with Marcel-waved hair, and diamond jewelry - a far cry from her aged, rustic look in Prem Kahani. The child's lace frock, hairband, shoes and socks are typical of Westernized, wealthy homes of the time. The lavish dressing table with three mirrors and casually arrayed perfumes add to the effect of material and social affluence.

This scene was very likely shot on the BT front lawns.

Flash forward

Saroj Borkar wears a fashionably modern sleeveless silk blouse with an abstract, geometric fabric design. Such a pattern with triangle shapes is reminiscent of Bauhaus commercial design, a cultural and aesthetic force that swept through trendy circles in early 20th century Europe. The Rais could not have remained oblivious to it during their time in Germany.

college

hunting

Shikaar

The sartorial splendor in this film merits a separate monograph! Devika Rani's gossamer sari with gold work and the modish, tiny blouse mark her as glamorous and modern. These minor excesses are narratively justified as we know that she is a serious student with maternal fantasies.

A striking circular shot that marks the distance between two moods and two visions of the future: apprehension versus anticipation on the one hand, and marital unfreedom versus carefree college education.

party playlist

In Prem Kahani we saw glimpses of contemporary anxieties about coeducational institutions. In Nirmala, this anxiety is transformed into romantic destiny. The 1930s social film frequently picked up the theme of love marriage as an agenda for social reform. The university provided a perfect location for the hero and heroine to meet; one of the rare public fora for young people to get acquainted.

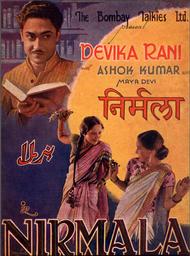

This is Ashok Kumar's eighth film and though not an accomplished actor yet, he does show a significant change from his early awkward performances. A contemporaneous review of the film said: “Ashok Kumar showed considerable improvement. Especially the early college scenes fitted him well. The lad is fast improving.” (FilmIndia, May 1938).

Ashok Kumar's increased competence and popular appeal is graphically indicated by his prominent positioning in the film's poster:

This conversation refers to an incident that has just taken place. The police, mistakes, shame, and forgiveness are mentioned but the viewer remains clueless about the exact reference. Is there a reel missing at this point?

This entire sequence refers to the mysterious missing scene, which is retrospectively reconstructed through cross-cutting. The parallel action is quite complex and spread across multiple locations. We have this phone cut as the mother calls up Maya Devi; Devika Rani returns; Lokenath and gang discuss the implications of Nirmala's actions; Ashok Kumar's friends accost him in the street; Devika Rani and Maya Devi stroll in her garden and dissect the incident; Ashok Kumar and friends do the same this time at his house.

This R-L tracking shot was taken in the BT compound. Thanks to production stills in the Wirsching archive we know that the camera was mounted on a sturdy trolley, R.D. Pareenja and another camera assistant were positioned on the trolley as camera operator and probably focus puller, one trolley guy pulled it backwards, 2 others kept hold of the wires, Josef Wirsching monitored the shot from the right of camera while Franz Osten stood closer to the actors on the left of camera. Sashadhar Mukerji, whose name is not mentioned in the credits, was present with what looks like a screenplay or continuity book in his hand. The microphone is suspended on a boom directly over the camera and just out of frame. Also note the sola topees/pith helmets worn by important crew members.

College classroom. Nirmala is portrayed as the only woman in the M.A. class. The scene is meant to set up flirtatious frisson between the two scholars, demonstrate Nirmala's coy wit, and drive home the idea of the destined couple. The scene transition is done with a visual fade-out plus a scripted dialogue fade.

Nirmala is tormented by the thought of an arranged marriage with Lokenath, a cruel man who tried to kidnap her earlier in the film. This song is in Ragini Todi, Taal Keharva and sung by Devika Rani herself. Note also the geometric fabric pattern of Nirmala/Devika's blouse, once again a marker of current global fashions adapted to Indian needs.

Flashback to the mothers' first chance meeting on the beaches of Puri. We see the two character actresses, Saroj Borkar and Pratima Devi play their real off-screen age for a change. Why does the film need this scene? The film denounces the practice of arranged marriage but the alternative cannot simply be random 'falling in love'. There has to be some solid justification for Nirmala to break off her long-standing engagement to Lokenath. This scene with its childhood augury sets the stage for a fated union of soulmates, a union that is stronger than any horoscope but blessed by the same divine authorities.

Now that the gods have blessed this marriage how can society raise objections?

Nirmala's friend, Pramila, teases her about her new life as a bride, far from her college girl days. But another friend counters that Ramdas himself a man of the "Nai Roshni", a modern man who will arrive at the wedding in a motor car not on a horse. All the teasing about modernity and post-marital change is done via sartorial metaphors. Fashion in this film not only provides visual spectacle or attraction (how can you miss the gold-embroidered velvet blouse and shimmering georgette sari Devika Rani wears here?) but also a conscious statement on the social milieu and its modern attitudes.

The presence of an Anglo-Indian extra in the group adds to the 'modernity' effect of these cosmopolitan college girls. However, we must also keep in mind that Anglo-Indian junior artistes were very common in the 1930s and a particularly vulnerable class of workers.

For a scene with at least 9 characters, the lighting is very restrained and artistic. Wirsching resists the convenience of high key lighting and goes with mood and realistic lighting effects. Today, 'bounce lighting' is the norm for scenes like this one in mainstream Indian cinema. All characters are uniformly lit and the kind of subtle gradations of light and dark you see here are missing.

A dramatic 'interval' point! Gun shots with smoke effects and synchronized sound effects have become a specialized field of work in the Bombay film industry. With the coming of color, there was the added attraction of watching synchronized blood spurts in time with the sound of the shots. These effects require precision, rehearsals, and a specialized talent which often comes under the supervision of the 'Fight dada' or 'Fight Master'. The quick editing, gun effects, and crowd choreography in this scene are impressive for the time.

Famous film critic of the time, Baburao Patel commented that “Several scenes before the interval are rather lengthy, but with every appearance of Devika Rani on the screen, disappointment becomes a pleasure…. The picture will run well due to Devika Rani.” (FilmIndia May 1938). The connection between a bankable heroine and a box-office success is not exaggerated. Actresses drove the economy of a risky pre-War film industry.

Wirsching's use of lighting in this scene is truly inspired. Notice how the significance of the detective, a brand new character in the story, is indicated not by literally putting him in the spotlight but by placing him in mysterious shadows. His air of enigma and gravitas are heightened by this lighting design. The shots are also composed unconventionally with high-angle OTS shots and material details like police files prominently lit in the foreground.

With this scene, the writers add another twist in this convoluted tale. While the film is basically about one woman's maternal instincts and sacrifice, the plot meanders into several elaborate explanations which are either unnecessary or too lengthy. Starting with the action scenes at the wedding, the film takes a brief detour into the territory of the thriller genre, complete with goons, guns, detectives, and criminal hide-outs.

A simple but effective plan of escape: pretend friendship and get the goons drunk out of their skulls. Ashok Kumar cuts a sorry figure in this scene. On the one hand, this silly escape strategy is hardly heroic or convincing. On the other hand, his singing talents leave much to be desired.

Looks like filmi cops arrived in time in the 1930s.

Nirmala and Ramdas sing a romantic duet. The set, compositions, and lighting are picture postcard perfect and match the sentiment of the song which speaks of sunflowers and nightingales.

Again, we see the use of a conversational style in the songwriting - seen earlier when Ramdas' friends tease him about the mysterious female topper. This conversational style of singing interspersed with a line of dialogue in perhaps most famously utilized in KL Saigal's "Ik bangla baney nyaara" song from President (1937), released a year before Nirmala:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L5mZMxnfxWYThe final tracking out shot in the song is a virtuoso act. As the trolley moves out from the two-shot to a wide frame, the night sky changes to early dawn! Such a drastic lighting change on-shot is truly remarkable for the 1930s. Devika Rani's last line draws attention to this fact: “Bhor ho gayi!”

This sense of fleeting time, the unnoticed transition from night to day, serves to underline the solipsistic bliss of the married couple.

Photographs as props recur in the films of the 1930s. However, in this scene we get a rare image of a photograph being taken, of characters posing for a photograph. Ashok Kumar asks Nirmala and Niti to pose: “Hold still/ Hilna mat.” And they obediently hold the pose, giving us a glimpse into photography etiquette and practices of the time.

As Ashish Rajadhyaksha helpfully reminded me, photography and photographs serve an important plot function in BT's Jhoola (1941) as well. Leela Chitnis' introductory scene features her on the eponymous jhoola/swing. A stranger walks by with a camera and asks to take a photograph. She reluctantly acquiesces and Shah Nawaz then proceeds to choreograph the pose, with instructions on her gaze, smile, hair. Once everything is in place he asks her to sing a line from the earlier song so that it looks natural. He then sends the portrait a magazine and it gets published on the cover. See this youtube link, from 09:50:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oiNIwIbOaPURefer also to Maya Devi's intro song in Prem Kahani where she sings to Ashok Kumar's photograph.

photography

Nirmala and Ramdas are overjoyed at the prospect of having a child. In this song they sing of the future, a storytelling device that presages trouble.

This film utilizes silence most effectively. Some of the most emotionally heightened moments are silent and gestural like this scene in which Nirmala looks expectantly at the doctor with great hope about the health of her newborn child. This 35 second mute sequence is catalyzed by a single gesture, the doctor's negative shake of the head, and Nirmala breaks the silence with her cry "Phir! Phir!"

The timeline view on indiancine.ma makes it possible to literally visualize stretches of silence and speech in a subtitled film. Take a look at the timeline that runs below the player in 'Editor' view.

Nirmala wrestles with her emotions in this cinematically striking scene. Through this dramatic monologue we get an insight into her psychological conflict even as a storm rages off-screen. Nirmala finally decides to leave her home and husband, in accordance with the astrologer's advice. Framed by solid darkness in this shot, Devika Rani seems removed from any worldly context. By the end of the shot she will have resolved to remove herself from the world she knows and walk into the darkness, adrift in the unknown...

Does this feel like a moment in a Douglas Sirk film? The grand staircase, the wind howling outside, the looming portraits of respectable ancestors who demand a male heir, the eerie shadows, the way these imposing interiors dwarf the tiny woman... these are elements of melodrama... and the spatial logics of architecture play a vital role in it.

Dattaram Pai, the editor, retains several seconds of lead-in footage of the storm set before Devika Rani enters the frame. This entire night storm sequence showcases some stunning lighting effects, from interior and exterior lightning flashes to shots of lightning in the sky.

Interestingly, one of the few criticisms of the film was that "the lightning in the storm was excellent but the thunder was ludicrously tinny." (Times Of India, Apr 29, 1938).

This is a single long take featuring the double ingenuity of brilliant lightning flashes as well as a lamp being switched on during the shot. These might not be very tricky lighting effects on their own but such single takes necessitate rehearsals, precision, and perfect timing.

Again, a very difficult shot using a track trolley to keep up with Nirmala as she struggles against the raging storm. Due to the combined needs of lighting for night exteriors, lightning effects, and wind machines for the trees, this shot would have required a major production set-up in terms of planning, equipment, and crew. Most certainly shot inside one of BT's sound stages.

More elaborate storm effects of trees and huts crashing. If you look at the timeline on the left, below the player window, you will notice each lightning shot clearly visible as a vertical white strip. This feature on the timeline view allowed me to quickly count that the number of bright lightning flashes seen in this entire night sequence = 14.

A comment on the evils of superstition - astrology in this case. Such narrative messaging is in keeping with BT's concern with social reform questions. However, the film doesn't quite follow through on this logic of skepticism since, for all practical purposes, Nirmala's third child does survive when the parents are separated and thus no superstitious minds will be converted by story's end.

The beggarwoman sings the same song that Nirmala and Ramdas had heard three years ago, "Jeevan hai sangram". The actress, Meera, has a beautiful clear voice, an effortless acting style and a very natural screen presence. Turns out that the earlier itinerant singer-fakir was this woman's father.

Impressed by Meera’s performance, a reviewer said that the beggarwoman “reveals a remarkably sweet voice as well as acting ability that should earn her distinction very soon… The song of the old beggar and Mira is already on ten thousand lips…” (Times Of India, May 27, 1938)

In case anyone has more information about this actress and singer, Meera, do get in touch.

The beggarwoman asks Nirmala to come live with her in the beggar's village. They are both single women (and one of them with child) with no resources and no family. The only place that can sustain such a duo without question or moral censure is a community of social and economic outcasts. Solidarity between two single women, minus male guardians, is a common trope in films. It is worth thinking this through economies of gender.

thesis1

Mumtaz Ali appears in time for a dance item.

The beggars are celebrating the arrival of a new child. Nirmala now goes by the name Nimmi and no one seems interested in whether her child was born out of wedlock. Those are niceties that torment the 'respectable' middle class. This is a world outside of moral hypocrisies, and their market-driven logics. The beggar's philosophy is stated most explicitly in this scene. They also discuss the value of a child in the affective hierarchy of charity. This idea will become a major plot point.

A pretty song about Krishna and his foster mother, Yashoda. Mumtaz Ali dances with simple, restrained kathak footwork and the instrumentation is kept bare. Camera framing plays a part in the dance choreography.

Baburao Patel, celebrity editor of the film magazine FilmIndia, had a typically sexist observation to make in his positive review of the film: “Devika Rani was easily the best but somehow she failed to impress me as a mother. Her light scenes were superbly acted. I think something more than mere acting is required to convince people in a mother’s role. One must perhaps radiate the divine glow of motherhood.”

Devika Rani was a renowned star by 1938 and many aspects of her private life were publicly known and discussed. That she had remained childless after several years of marriage to Himansu Rai was the cause of some speculation. In this comment, Patel betrays a conservative attitude to femininity and motherhood. More significantly, he reveals the immense contradictory pressures felt by actresses at the time and even today. On the one hand, married actresses who have never had children are considered incapable of nuanced portrayals of motherhood. On the other hand, the sexual lives of unmarried actresses is a matter of great public concern and moral debate.

Fragments of the screenplay of Nirmala are available in the Dietze Archive. Below is a dialogue sheet for this scene and the next, handwritten in Nastaliq. Such paper artifacts have a profound significance for the study of histories of language and screenwriting practices in the early Bombay talkie industry. The scenes are numbered 135 and 135A and appear to have been handwritten for the immediate purpose of rehearsal and memorization on-set.

This film, Nirmala, was clearly constructed to showcase and exploit Devika Rani's talent and popularity. Rani's fans were legion and many idolized her as the epitome of perfection. Here is a typically gushing review of the time: “Devika Rani acts brilliantly, putting over a portrayal or rather a succession of portrayals with a consummate art and the smooth easy dignity that characterizes her genius. As the young maiden, the college girl pliant yet resolute, the playful companion and the charming daughter and the happy bride, the wife pathetically eager for motherhood, the bereft mother crazed by the loss of her child and the weary old woman searching the world for the baby that was snatched from her bosom, she presents a succession of brilliant cameos that run together upon the thread of her personality to present the evolution of a perfect and eminently lovable woman.” (TOI Apr 29, 1938).

Ashok Kumar names the dog, Bulldog Drummond, after the world-famous fictional character created by British author, HC McNeile. The figure became internationally known after a series of novels, plays, and films were centered on his character of a bored WWI vet seeking sensation and adventure.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bulldog_Drummond#Films

Very efficient time transition effected through a dissolve and keeping the exact same camera framing and lensing.

Another scene featuring posed amateur photography. This time the time transition was less overt but effective nonetheless. In a storyline with such meanderings, it is hardly surprising that now, after a run time of almost two hours, the filmmakers decide to economize with time.

With the discovery of the old photograph it is established that son and grandson looked identical in their infancy. Thus the final reunion/recognition of the family unit is set up.

Devika Rani's hair, costume, and make-up as an old beggarwoman are elaborate and very skilled. The wooded location chosen for this scene appears to be the same as the one used in the "main ban ki chidiya" song in Achhut Kanya 91936). This might have been a part of the BT property in Malad, then still a forested area and quite rural.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pxttMH3oq_o

The dramatic payoff scene begins. This scene also showcases Devika Rani's histrionic range and capabilities. Dramatic irony is fully exploited as Devika Rani, the mother, unknowingly strikes her darling son, and Ashok Kumar, attempts to strike his own beloved wife.

Another thrifty time transition which skips the emotional and practical logistics of recognition and reunion.

Life comes a full circle as husband, wife, and child are reunited. A flashback and a familiar song serve to underline this cyclical trajectory.

Indiancine.ma requires JavaScript.