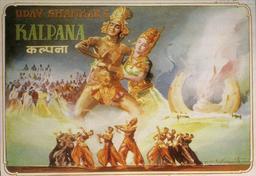

Kalpana (1948)

Director: Uday Shankar; Writer: Uday Shankar, Amritlal Nagar; Producer: Uday Shankar; Cinematographer: K. Ramnoth; Editor: N.K. Gopal; Cast: Uday Shankar, Amala Shankar, Lakshmi Kanta, G.V. Subba Rao, Birendra Bannerjee, Swaraj Mitter Gupta, Anil Kumar Chopra, Padmini, Lalitha

Duration: 02:17:45; Aspect Ratio: 1.333:1; Hue: 93.400; Saturation: 0.015; Lightness: 0.296; Volume: 0.182; Cuts per Minute: 13.684; Words per Minute: 34.576

Summary: A dance spectacular, four years in the making, orchestrated by India’s most famous modern dancer (and brother of Ravi Shankar). The narrative of the surreal fantasy is embedded within a framing story of a writer telling a story to a film producer, who eventually declines to make the movie. The writer tells of Udayan (Shankar) and Kamini (Kanta) and the young man’s dream of establishing an art centre, Kalakendra (a fictional equivalent of Shankar’s India Cultural Centre at Almora) in the Himalayas. Shot in the Gemini Studios in Madras, this ode to creative imagination mobilises the vocabulary of traditional dancing, which doubles as a metaphor for the dreams invested in the newly independent India. The choreography was specifically designed for the camera, with semi-expressionist angles and chiaroscuro effects, and became a model for later dance spectaculars like Chandralekha (also made at Gemini and shot by Ramnoth, 1948) and the dream sequence in Raj Kapoor’s Awara (1951). For many years, the unusual film was seen as exemplifying a successful fusion of Indian modernism and the cinema. Shankar, who had danced with Pavlova, was lauded by James Joyce in a letter to his daughter: ‘He moves on the stage like a semi-divine being. Believe me, there are still some beautiful things left in this poor old world.’ A 122’ version was shown in the US although one reviewer noted that the Indian government seemed reluctant to let it be seen abroad.

Censor Certificate

censor certificate

Special musical effects: includes Ali Akbar Khan and 'Ravindra Shankar'

Introductory statement: 'I request you all to be very alert while you watch this unusual picture - a Fantasy. Some of the events depicted here will reel off at a great speed, and if you miss any piece you will really be missing a vital aspect of our country's life in its Religion, Politics, Education, Society, Art and Culture, Agriculture and Industry.

I do not deliberately aim my criticism at any paricular group of people or institutions, but if it appears so, it just happens to be so, that is all. It is my duty as an Artist to b e fully alive to all conditions of life and thought relating to our country and present it truthfully with all the faults and merits through the medium of my Art. And I hope that you will be with me in our final purpose to rectify our own shortcomings and become worthy of our cultural heritage and make our motherland once again the greatest bin the world.

- UDAY SHANKAR

This was a controversial statement, and much was made of who he might be referring to, both offscreen and on-screen.

At a 'Thunderstruck' Film Studio, a scenarist is trying to persuade a movie producer to make a film about the 'needs of the country'. Almost more than any of the 'War-effort' realist films of the year (the others being Dharti ke Lal, Neecha Nagar and Dr. Kotnis Ki Amar Kahani, all made the same year), Kalpana consciously references the circumstances of its actual making: the widespread perception of the heartless inability of India's movie producers to make films about 'reality' (as a part of the War effort).

In his 'Report' on Kalpana and its finance, Uday Shankar writes: 'Those were the days when the production of cinema films were strictly controlled; the film racketeers having gong good time selling licences in black market and the established film producers and their organisations, preventing those new to the line from getting licences. Those Producers all over India, howled, barked and protested vehemently trying their best to influence the officials in Delhi in preventing me getting a licence'

(see note below):

The pre-history, of the child Udayan and the child Uma: the balletic dance performance idiom already established. What is remarkable about the idiom is the way the film can move seamlessly between three states: the 'real' story, the performance on stage, and the dream: something it will do throughout.

"A typical exercise would present the opportunity for the students to call upon all of their senses and then respond to the movement in relation to their own experience and at their own pace. For example, a movement would be

presented to the students. Rather than merely imitating it until the body had kinesthetically memorized the movement, the students were asked to analyze the movement by locating it in their sight (to see the movement in space). Then, they were asked to place it into a basic, identified movement pattern (the arc theory). The student then executed the

movement within his own spatial arc, sensing the stress and release within the body, identifying those areas affected and in what way, so that the distinction of stress and

release in the muscles was noticeable in order to identify the

movement kinesthetically as well as visually through direct observation - Ruth Abrahams, 'The Life and Art of Uday Shankar (NYU PhD Thesis, 1985: pg 178-179)

The phantasy of the 'bada shaher' - the family of the child Uma moves to the city, triggering off a brief fantasy for Udayan, as to what the big city holds. The first of the film's several very famous multiple-image montages: his face on which are superimposed the images of performance in the city.

The first of the dream sequences: Udayan is admitted into school, where he encounters a particularly vicious and violent teacher, triggering off a fantasy in full Kathakali.

Uday Shankar/Udayan's entire imagination of the enlightened new-generation art institution was defined against the perceived tyranny of the prevailing educational system, which kills the creative 'dreams' of children. This sequence is also the key moral framing of the problem, as the 'film-within-the-film' also seeks to show, using the narrator/scenarist's voiceover.

Udayan grows up. Interestingly, his first art seems to be watercolour, very much in the Bengal School idiom. He is now sent to Benares for further education.

Benares, and the first school: Uday Shankar himself considered starting his first dance centre in Benares, and also outlined in 1937 his initial imagination for it:

The second fantasy: also one of the film's most famous sequences: the dance of the hand. A shot, presumably set in hell, has Udayan 'fall', in atonement for the loss of a year. The entire dance, involving several dissolves and superimpositions, also introduces Amala Shankar into the film: the grown-up Uma.

Even before turning filmmaker, Uday Shankar was fascinated with multimedia representations on stage. "Shankar's interest in multimedia presentations began at Almora, and most of his key works are in the film. Multimedia included his fascination with combining "stage and screen effects with old-fashioned magic and

illusion" (Ruth Abrahams, 'The Life and Art of Uday Shankar, NYU PhD Thesis, 1985: pg 202)

First proper introduction of Uma (Amala Shankar): Udayan recognizes her from his dream. The context for the staging of the first dance ballet in Benares

painting

The performance rehearsals, and the deal with the manager of the

Shakuntala Theatre. The theatre is as corrupt and absent in vision as the cinema, as we shortly see with the disastrous consequences of that arrangement.

The first performance. This was Uday Shankar's very famous "Tandava Nyritta", originally staged with Shankar

as Shiva, Simkie as Parvati, Kanak Lata as the maid-servant, Joya, and Debendra as the villainous elephant-demon,

Gajasur. This, says Abrahams, was the 'first major work choreographed by Shankar after his extensive trip throughout India, and it reflected aspects of specific dances and information about India's folk forms that he acquired during his travels'. The most noticeable change was 'incorporation of the kathakali style of hasta mudra. An examination of Shankar's use of this symbolic hand gesture system, which conveys sentiments and the narrative of the

dance through gesture rather than vocal language, reveals major departures from established positions in the structure of this system' (Ruth Abrahams, 'The Life and Art of Uday Shankar', (NYU PhD Thesis, 1985: pg 119-120)

The relationship between Uma and Udayan grows: establishing the somewhat distinctive camaraderie that the Almora school would later develop, also framing the internal tensions within the troupe.

The fight between the financier and the troupe continues the interest in merging the 'real' sequences with the stage ballet. The manager of the theatre is clearly trying to swindle Udayan,. The fight that breaks out is shown in fully balletic style, with mirrors and glass. K. Ramnoth's expressionist lighting continues Shankar's fascination with dark interiors and spotlit areas.

Uday Shankar's ballet of the famine: direct reference to 1943, documentary film, and the image of starvation, migration and poverty. This sequence was explicitly imagined for the film, and also brings this film alongside both Dharti Ke Lal and Chinnamul as films that deal with the famine.

Nehruvian nationalism

Introduction of Kamini, and several further motifs: the famine of the previous sequence as against the rural plenty of Indian dances. Kamini, as the jealous third woman, who will keep trying to corrupt Udayan by dragging him into her Bombay world, also frames Udayan/Uday Shankar's fascination with what she calls 'primitive' peasant dance as against the Bombay to which she will take him in the next section.

Introduction to Bombay: the city which has the 'combined filth of all of Europe and America' stuffed in it. The troupe has presumably travelled through Calcutta and Delhi to arrive here.

The first proper introduction of the 'blocks' style that Uday Shankar had devised for the film. According to Abrahams, Shankar devised an idea of using 'mammoth, rotating, interlocking block formations', mainly for financiaL reasons, The idea came to him apparently 'as he watched his young son, Ananda, (Shankar) play with a set of building blocks'. The 'simplicity of the constructions and the suggested possibilities of mobility and variety provided the model by which Shankar created the sets for his film. These were complemented by designs created on slides by Amala' (Ruth Abrahams, 'The Life and Art of Uday Shankar (NYU PhD Thesis, 1985: pg 199)

First confrontation between Udayan and the unrepentant'y bad Kamini: the end of the sequence on their shadows is a form that Shankar would also follow later in the film.

Confrontation with Kamini grows, but Udayan agrees to meet the city's elites. Sharp source lighting and large shadows continue.

The encounter with the city's bourgeois elites: the sequence culminates in the industrialist and mill owner who,

Metropolis-like, wants to convert all his workers into machines. The film launches into his most famous ballet, the 'Ballet of Labour and Machinery'.

The Indiancine.ma Khazana

Udayan's fantasy: dissolving into the Ballet of Labour and Machinery.

Originally staged in 1941, this ballet also inaugurated Shankar's first experiments with multimedia "events" at Almora.

Urmimala Sarkar Munsi writes about this sequence:

"The extensive sets used in the scene where Shankar takes up the issues of urbanization, industrialization the exploitation of the workforce, human life as machine, the rural–urban balance.. Using simple wooden boxes of different dimensions and projections of parts from the typewriter, he planned and created sets of the semi-dark interior of a factory,

using mechanical movements to depict the mechanization of life. More noteworthy than the sets or the depiction of the thematic is the range of movements, created for the representation of the total scenario of machines and the workers, not drawn from any particular existing movement vocabulary but actually created for the specific purpose of enacting the scene. Extensive use of choreographic designs at different levels and complex synchronization of multiple rhythms and movements establish the activities of a factory and changed life of the people who are still in a dilemma over the choice of industrial work over agriculture. In this particular scene, a striking balance is achieved between movements from the daily lives of ordinary people and postures and technique from different existing movement vocabularies of Indian dance, thus enhancing the creative moments and also providing a huge range of non-grammatical movement patterns which till then were never thought to be possible ingredients for creating a dance. Movements from daily life — eating, shaving, walking, sitting, running — have been utilized in two particular ways: first, to build a stylized movement vocabulary out of everyday movement practices, and second, to incorporate the everyday movements into the story as tools to help the depiction.' (Urmimala Sarkar Munsi, 'Imag(in)ing the Nation: Uday Shankar’s Kalpana' (in Munsi

Stephanie Burridge ed. Traversing Tradition: Celebrating Dance in India', New Delhi: Routledge, 2011, pg 137-139).

Abrahams writes, 'Themes and structures varied among the familiar Indian ballets, extravagant shadow-plays, and film. The first production included two ballets entitled, "Labour and Machinery" and "Rhythm of Life." These were Shankar's only works that reflected current themes and commentary on social injustice. The pieces focused on the social plight of Indian working classes and their struggle to cope with the infusion of technology into the traditional society and the ensuing confusion industrialization wrought on their lives. While analyzed by some as Marxist statements on behalf of the proletariat classes, the works were more aptly conceived as metaphors for the struggle between tradition and modernity. In "Labor and Machinery," particularly, the staging utilized avant garde costumes that annihilated the individual qualities of the performers/ workers and utilized sets of massive and ominous proportions A sense of the Sisyphesian futility of the workers' lives sensitively, but powerfully conceived by Shankar' (Ruth Abrahams, 'The Life and Art of Uday Shankar (NYU PhD Thesis, 1985: pg 185-186).

Udayan denounces the elites and walks out. One of them however, simply to prove that the elites are not inhuman, gives him a cheque. Udayan throws it ino the trash, but a street urchin rescues the cheque and gives it back to him. His dance academy can now happen.

He asks for forgiveness from the Master, presumably for having strayed off the straight and narrow in Bombay: Udayan's own fascination with the cinema - revealed in the film's opening sequence, and once more when he agrees to Kamini's suggestion that they consider making a movie to raise funds (reference to Kalpana itself) - will however keep seeing him make such compromises and atone for them.

Udayan's dream institution. Of interest is the presence of radio in this: it will consist, says one announcement, of "experimental radio station, library, museum, gymnasium, national theatre". The sequence leads on to the very famous 'Sadiyo Ki Behoshi' song and the puppet dance.

Return of Kamini: who follows him to Almora

Udayan's theory of education.

Urmimala Sarkar Munsi writes:

"Shankar also included a scene which had less of dance and more of dialogue, questioning the means and the ends of the existing education system where a group of male and female students wearing graduation gowns come out in two gender-specific lines. The scene hints at the implied equalizing effect of modern education where the telltale signs of class, caste, gender, and religion are overshadowed by the effect of the formal degree. Shankar’s hope of a caste/class/gender less society becomes clear here where he puts emphasis on modern education as being the path to development. At the same time his apprehension about the misuse of an education system, which could create more inequality if the goals are not clearly defined, is also conveyed. The students are shown to be walking out as their fathers are waiting. The fathers start expressing their delights at their sons’ rise in the social status as graduates and their increased market value by saying things like, ‘Great, my son, you are so qualifi ed that I can ask for Rs 50,000 for your dowry now!’ The continued scene portrays the young generation’s confusion and response at their fathers’ reactions and at the ends of education by all of the graduates pointing to a huge question mark on the screen behind and saying to the fathers in unison, ‘We respect you, but this is our future.’ This is followed by a crowd of female graduates, all with their degrees rolled up in their hands, expressing their concern about the means of education. The use of vernacular languages instead of Hindi marks the dialogues where they shout in visible act of protest, ‘We do not want such education’ and ‘It is impossible to build a nation without a national education policy’. The scene culminates in all the students throwing their degrees up in the air, in a clearly portrayed act of protest. The next, continued sequence is of the same group of women, dressed in urban, everyday clothes (with a deliberate projection and assertion of independence in the choice of clothes, the walk, with the head held high, without any cover on their head, and a very obvious self-assured body language), walking down what looks like the fashion show ramp of today. They face a group of older men, whose

traditional garb hints at their social position as conservative, who try laying down ‘rules of dos and don’ts’ to the women"

(Urmimala Sarkar Munsi, 'Imag(in)ing the Nation: Uday Shankar’s Kalpana' (in Munsi Stephanie Burridge ed. Traversing Tradition: Celebrating Dance in India', New Delhi: Routledge, 2011, pg 141-142).

Second staging of the Tandava Nritya, in a more developed form

Shankar's most pronouncedly nationalist ballet: of national integration, of a multilingual India, all coming together to ensure no more suffering of 'Mother India'

Discussion of finances: Uma's plan for a festival is accepted, Kamini's proposal for making a movie with Bombay producers rejected.

It is significant that this sequence is directly contrary to what actually happened at Almora. Speaking of a crisis that affected the Centre in 1944. Abrahams writes:

"Artistic differences emerged between Shankar and the professional company members as they opposed Shankar's desire to curtail concert tours and choreographic developments in favor of a film project. Simkie, Zohra and Shirali, the oldest and artistically strongest members were particularly adamant about the suggested shift from stage performance to film production. The conflict was not contained among the professionals, but filtered down to the students who variously sided with their favorites. The rifts created within the different levels irrevocably damaged the school's stability.

At a meeting in Bombay on January 25, 1944, Shankar disclosed his plans to discontinue the school. Present were Sir Chinubhai, a member of the Board, Shankar, Shirali and George Birse. The dissolution statement outlined four reasons for Shankar's actions:

1. The end of the five-year experiment had more negative than positive results caused by the remote location.

2. The staff at the school and certain members of the Trust were incapable of contributing to the development of the Center as originally outlined.

3. The work at the Center no longer represented the original intention due to a lack of experienced educators on staff, which resulted in an unbalanced program of study that emphasized only the dance, rehearsals and performance.

4. The calibre of students had declined from that of the first enrollment, which had a negative effect on morale.

Shankar's alternative plan called for the termination of the school and the transfer of his activities to a location

more accessible to Bombay. He then suggested that after entering into negotiations with a film company that would produce the project he had previously outlined as a professional and personal priority, he would spend a year to reorganize a new venture that would eventually develop into a film production company.

(Ruth Abrahams, 'The Life and Art of Uday Shankar (NYU PhD Thesis, 1985: pg 182-184)

Conflict between Uma and Kamini erupts into physical violence: Kamini's hysteria also now directly in the open.

Kamini tries to make further trouble - she has an affair with Madan, and tries to take him away. Uma hears them. The use of shadows as locations for working out secret deals, and also as backdrop for a confrontation continues.

Childhood pre-history of Udayan and Uma revealed: astonishingly, he seemed not to know. Uma's plan to not tell him is partly as a result of her enduring doubt about her ability to stay in the School.

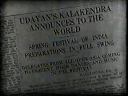

Brief documentary-propagandist outline showcasing what the Spring Festival will comprise: focus on indigenous dance practices.

Love story now firmly established, even as Kamini watches.

The indigenous costume law: an Indian wearing a suit is not permitted in.

The strong emphasis on radio: live radio broadcast of the Spring Festival, in all Indian languages.

Urmimala Sarkar Munsi writes:

Let us take, for instance, a scene about the dream institution of Udayan. A huge number of people have arrived for a public performance. The princes of private princely states start arriving on their palanquins and special careers. Many people in western clothes, both Indian and foreigners, arrive alongside scantily clothed peasants, villagers and workers. The gates to the auditorium are low. People have to crawl in. When asked the reason for this, one of the volunteers explains the necessity to bow down to art and artistic ndeavours regardless of their social or economic positions. The satirical and comic elements are made evident in the way the heads of the princely states are dressed or are seen to be exercising their power, or through their reaction and implied position about being subjected to common Indian legislative regulations. Shankar’s personal opinion about the special powers of the princely states and the national debate around these issues are incorporated in the imagination through the dream of Udayan. During the same performance, the Indians wearing western clothes are barred from entering and are asked to come back wearing national costumes, while the westerners wearing the same kind of clothes are allowed in. The role of an ideal citizen is etched out alongside the expectations from the soon-to-be- independent nation.

(Urmimala Sarkar Munsi, 'Imag(in)ing the Nation: Uday Shankar’s Kalpana' (in Munsi Stephanie Burridge ed. Traversing Tradition: Celebrating Dance in India', New Delhi: Routledge, 2011, pg ).

Final and most elaborate version of the 'Tandava Nritya: the showpiece of the entire Almora programme.

Final confrontation between Uma and Kamini: Kamini's murderous attack on Uma ends in a curious ethical dilemma, which will frame much of the remaining part of the film. Is Uma now to realize her selfish desire - which would in the end make her no different from Kamini - or will she realize that the ideal of the School, and Udayan's commitment to his art, is to transcend her love, forcing her to step back and, perhaps, to leave? This test will constitute the film's eventual climax.

Uma/Amala Shankar showcasing her abilities at Manipuri

The complete range of India's several national dances, from Raas-Garba to Kathak.

Uday Shankar's startling combination of dance and the peasantry - the introduction into the dance of the tractor and the plough - with the radio always playing a role in between - are major, daring connections between dance and documentary realism.

The dancing gets more frenetic, and the crowd gets more excited. The Maharajahs in the audience make for a curious additional presence, especially in the fashion parade that will soon follow. The money pours in. This may well be Shankar's critique of the Almora institution's tendency to accept money. It will become more grisly with the ogling Maharajahs in the next sequence - and Madan's emotional meter asking them to 'bring on the girls' because the audience is getting restless.

Comment on women's freedom, but it will take a curious turn in the following sequence.

The frenetic pace culminates in a veritable cabaret. The Maharajahs, in a delirium of excitement, pour money into the Kalakendra's coffers. udaual seems to go along with this entirely. And then a curiious development: he rolls down the stairs, and has a final, feverish dream.

Udayan's dance to win over Uma - the Shankar-Parvati refrain returns, and works through several dance forms and emotions, until he is at the foothills of the Himalayas (all this is Udayan's reverie). He is now faced with a test.

A curious test - Udayan, as the Purusha, has to carry Uma, as Prakriti, to the top of the mountain: he shall not fall or waver. This is a test put to him, not by believers, but by those who feel that one has to believe to keep the people on one's side.

Udayan apparently succeeds in his task, which is to take Uma to the top of the mountain without wavering. We next have to deal with Uma's anxieties as well.

Uma sees the unconscious Udayan. She has finally killed him, as Kamini - her scheming, screaming, alter-ego - says to her. Kamini is now free, and tries to take the hapness Madan with her, but they fall into the valley and die. Uma, finally rid of her evil desires, kills herself.

Udayan, who is not dead but merely unconscious, now wakes up and sees the dead Uma. He accuses the god Shiva of being uncaring in his destruction. Shiva now brings Uma supoposedly back to life, but she will now only live on "within" Udayan. Udayan himself, his dream over, now comes back into consciousness.

Udayan has exorcised his ghosts, and now can confidently ask her to marry him. Uma is however not yet done.

The film's cynical ending - everything ends in a frenzy of money: the cabaret dance, the slavering Maharajahs, Udayan asking Uma to marry him, the theatre and film producers, and the money flowing into the coffers of the dance academy become part of one frenetic montage of burning images.

The scenarist's lament

Indiancine.ma requires JavaScript.