Summary:

Having built his own studio at Chembur in Bombay with the profits of

Barsaat (1949), Kapoor launched his most famous film, collaborating with the unit most closely associated with his work: scenarists

Abbas and

Sathe, song-writers

Shailendra and

Hasrat, art director Achrekar, cameraman

Karmakar and composers

Shankar-

Jaikishen. Set in

Bombay, the plot concerns Raju (

Kapoor), the estranged son of Judge Raghunath (

P. Kapoor), who finds a surrogate father in the criminal Jagga (

Singh), the dacoit who caused Raju’s mother (

Chitnis) to be thrown out of her home. Raju eventually kills Jagga and tries to kill Raghunath, before he redeems himself in the eyes of the judge and wins the love of his childhood sweetheart, Rita (

Nargis), who is now the lawyer defending him in court. The very intensity of the oedipal melodrama, enacted by the Kapoor family itself, spills over into a kind of hallucinatory pictorialism (the

dream sequence, the

prison sequence at the end, the design of the judge’s mansion) and underpinned some of the most remembered songs of the 50s (Awaara hoon, Ghar aya mera pardesi and Dum bharke udhar mooh phere, o chanda).

The spectacular 9’ dream sequence which took three months to shoot was apparently added on at the end, to hike up its market value.

The spectacular 9’ dream sequence which took three months to shoot was apparently added on at the end, to hike up its market value.

This was also Kapoor’s first fairy-tale treatment of class division in India, whose nexus of authority (power, patriarchy and law) explicitly excludes the hero. Its main tenet, presented through Raghunath, is the feudal notion of status: ‘the son of a thief will always be a thief’, a view that villain Jagga sets out to disprove by making Raju a thief. Raju’s patricide (he kills Jagga and is arrested for attempting to murder Raghunath) tries to break out of the contradiction set against an alternative, post-colonial, reinvention of an infantile Utopia in which everyone can fully ‘belong’, a condition symbolised by Nargis who is both the hero’s conscience and reward. Kapoor’s later treatments of the same contradictions increasingly took on the ‘frog prince’ fairy-tale structure (Shri 420, 1955; Mera Naam Joker, 1970), mapped on to the middle/working-class divide. The film launched Kapoor and Nargis as major stars in parts of the USSR, the Arab world and Africa, while the US briefly released an 82’ version. Nargis’ appearance in a bathing costume is widely but wrongly believed to be the first erotic swimsuit scene. That cliche had earlier been deployed by Master Vinayak in Brahmachari (1938). Gayatri Chatterjee (1992) published a book-length commentary on the film.

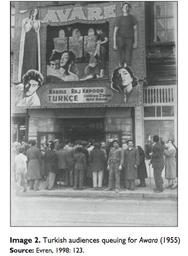

The international life of Awara

Awara was a huge hit not only in india but in many parts of the world including Russia, China, Egypt, Turkey etc. See, Ahmet Gurata, “The Road to Vagrancy”: Translation and Reception of Indian Cinema in Turkey, [1(1) 67–90]

Awara was a huge hit not only in india but in many parts of the world including Russia, China, Egypt, Turkey etc. See, Ahmet Gurata, “The Road to Vagrancy”: Translation and Reception of Indian Cinema in Turkey, [1(1) 67–90]

Awara Chinese (Pad.ma)

Awara Turkish (YouTube)