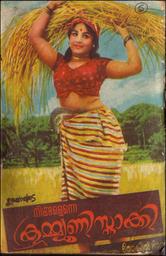

Ningalenne Communistaaki (1970)

Director: Thoppil Bhasi; Writer: Thoppil Bhasi; Producer: Kunchako; Cinematographer: C. Ramachandra Menon; Editor: S.P.N. Krishnan; Cast: Sathyan, Prem Nazir, Sheela, Ummar, Jayabharati, Kottyam Chellappan, S.P. Pillai, Thoppil Krishna Pillai, Lalitha, Adoor Pankajam, P. Rajamma, Vijayakumari, Alumoodan, Kundara Bhasi

Duration: 02:17:34; Aspect Ratio: 1.500:1; Hue: 267.195; Saturation: 0.002; Lightness: 0.379; Volume: 0.211; Cuts per Minute: 5.473; Words per Minute: 78.993

Summary: Bhasi’s version of his own landmark socialist realist play (1952) popularising official CPI ideology in Kerala. Gopalan, after obtaining a college degree, devotes himself to trade union work to the distress of his father, the tradition- bound Paramu Pillai whose family fortune has been eroded. Gopalan and his working-class friend Mathew oppose the evil landlord Kesavan Nair’s schemes to obtain ever more land through fraud and intimidation. They are beaten up by the landlord’s hired thugs and hospitalised. In the end, Paramu Pillai, radicalised by the need to defend himself against the landlord, emerges from his house brandishing a red flag and joining the collective struggle against exploitation. A subplot has Gopalan in love with Kesavan Nair’s daughter although the one who truly loves him is Mala, the daughter of a poor, aged tenant farmer also about to be evicted by the villain. Bhasi went on in the same agit-prop vein, backed by the CPI, with e.g. Enippadikal (1973).

Satish Poduval adds:

The film version of "Ningalenne Communistaaki" (1970) was based on Thoppil Bhasi's landmark play written in 1951 (published in 1952 under the pseudonym 'Soman' as Bhasi was then in hiding for his alleged involvement in the Sooranad case). The play had originally been written as a 'prose-play' meant only to be read, but the young communist activists associated with the fledgling Kerala People's Arts Club (KPAC) reworked it in collaboration with Bhasi--adding melodious songs, credible dialogues in earthy idiom, nuances to characterization, deepening the melodramatic polarization in several scenes, entwining the critique of feudalism with patriarchal control of women--and put it on stage in Thattassery Sudarsana theatre, a thatched hall at Chavara near Kollam (Quilon) on 6 December 1952.

Robin Jeffrey notes what followed:

"In March 1953, the District Magistrate of Trivandrum, instigated by the Congress government of Travancore-Cochin state, banned [this play]. A year later the High Court of Travancore-Cochin ruled that the ban was invalid. Meanwhile, the play was widely and illegally performed, its published version sold well and its songs 'were on the lips of street boys and peasant urchins for...years.'" [...] "The popularity of the play...stemmed from its deft combination of familiar things, both old and new. Musical drama was an old form of rural entertainment; but the content--the struggle of the rual poor against police and landlords--was recognizable daily life to many audiences. Even for town-dwellers, the subject was as topical as the daily newspapers... [The play] both symbolised and extended Kerala's changing political culture. The fact that audiences responded so enthusiastically indicated that they sympathised with the ideas of equality and struggle that the play sought to convey. The play itself not only reinforced the legitimacy of such attitudes but presented them to people who might not have encountered them before. The efforts to ban the play testify to its effectiveness."

Darren Zook too suggests that "it is not too much of a stretch to suggest that the popularity of the communists, which allowed them to capture state power in the elections of 1957, stemmed largely from the popularity of Bhasi's play and its songs."

Performed over 10,000 times since 1952, this is the most widely-staged and influential play from Kerala--it has also been staged in several cities across the country including Delhi, Mumbai and Ahmedabad.

There have been several critical 'counter-plays' written in response to Bhasi's classic. The earliest were "Njaanippakkammoonishtavum" (I Will Become a Communist Now, 1953) by Kesava Dev, and "Vishavriksham" (Poisonous Tree, 1958) by C.J Thomas. During the mid-1990s, Civic Chandran was sharply critical of the Communists's legacy in "Ningalaare Communistakki" (Whom Did You Make a Communist, 1995) from an ultra-left and dalit-feminist viewpoint, provoking a bitter clash with the KPAC and the CPI cadres. Thoppil Soman (Bhasi's son) wrote two plays that have extended the debate around the issues raised by its critics: "Ningalenne Communistakki Indra Sadassil" (You Made Me a Communist in Paradise, 2004) and "Enum Ente Thambranum" (Me and My Lord, 2008).

The film version, unlike the play, was directed by Thoppil Bhasi himself and the actors were not KPAC amateurs/activists but major stars from the Malayalam industry. The popular songs of the play by KPAC stalwarts K.S. George and K. Sulochana were replaced in the film by melodic numbers by Yesudas and P. Susheela. Although the film version was also commercially successful, its influence on the social and political life of Kerala cannot be compared to what the play achieved in the 1950s.

Udaya Studios, one of the oldest film production studios in Kerala, was established in 1947 by director-producer Boban Kunchacko (1912–1976) and film distributor K. V. Koshy in Pathirappally, Alappuzha (Alleppey). The studio played a key role in the shifting of the Malayalam film industry from Chennai (then Madras) to Kerala.

CCK 1

Writer-director Thoppil Bhasi addresses the audience as a living legend in Kerala's public life. He observes that the KPAC's great contributions are recognized even by national leaders such as Jawaharlal Nehru--a significant reference, and a measure of the sea-change in public life, because in 1954 when Bhasi contested the Travancore-Cochin Assembly election as a Communist Party candidate, Nehru had publicly called Bhasi a "murderer" (as he was then an accused in the Sooranad case). Bhasi was acquitted and went on to win two elections for the Communist Party in 1954 and 1957, before withdrawing from politics to concentrate on writing. In the early 1960s, Nehru had personally attended KPAC's presentation of Bhasi's play

"Puthiya Akasham, Puthiya Bhoomi" (New Skies, New Horizons) in New Delhi and praised the team's achievements.

Bhasi notes with regret the split in the Communist Party in 1964. Most KPAC members were associated with the CPI, and used to donate Rs. 40 every month from their salary of Rs.500 to the party. During elections, and whenever the party faced financial problems, KPAC gave the party the entire proceeds from its performances.

Bhasi also thanks producer Boban Kunchacko whose Excel Productions had adapted several of Bhasi's screenplays during the 1960s, and who through this film enabled Bhasi to make his debut as film-director (he went on to direct thirteen more).

As the film opens, we segue from a stage to a screen setting and are introduced to the first primary set of characters. Paramu Pillai is an old and arrogant Nair patriarch who alternates between waxing nostalgic about his family's former days of glory and berating his wife Kalyani, son Gopalan, and daughter Minakshi for the family's current decline. His lower caste neighbour Pappu listens to his rants patiently. Paramu Pillai is especially resentful of Gopalan for being a communist activist organizing lower caste peasants and challenging the rich relative, Kesavan Nair the landlord.

The next sequence introduces two other key sets of characters--Kesavan Nair, the scheming and lecherous landlord, assisted by his wily but comical lackey Velu; and the vivacious pulaya (untouchable caste) peasant woman Mala, and her father Karamban--both of whom are tenants of Kesavan Nair; they are also members of the communist party and provide their hut for its night classes. Mala rebuffs Kesavan Nair's amorous advances, and the angry landlord decides to act against his "upstart" tenants.

Kesavan Nair and Velu cross paths with the communist leader Mathew, and rudely seek to intimidate him but he answers them back. Since Mathew has arrived from Vayalar, there is a bitter debate about the recent massacre of protesting workers by the police at Punnapra-Vayalar. The journalist K.C. John has described this historic event thus:

"Martial law was proclaimed by a royal order on 25 October 1946, after a day of intense insurrectionary activity by hundreds of spear-carrying proletariat in which a police camp with 40 policemen at Punnapra was raided and arms seized. For four bloody days the army and the police opened fire on the workers and a large number of them were killed, mauled or mowed down. The wooden spears could do very little against the guns that roared all over Alapuzha and the adjoining villages of Punnapra and Vayalar. No accurate figures of death were ever collected."

Gopalan visits the college where Sumam--Kesavan Nair's daughter--studies, and urges them to contribute to India's newly-won freedom by fighting landlordism. It is clear that Gopalan and Sumam like each other, and they sing a song written by Gopalan.

Karamban tells Mala how her mother had been assaulted to death by Kesavan Nair and his goons for rejecting his sexual advances. Mala says with determination that such a fate would never befall her as "our people" (pulayas trained as communists) were not so helpless now. Gopalan visits them to continue teaching her. She admires and loves him, while he comes across as a patronising leader who cannot really see what this education means for Mala.

The song "Pallanayarin Theerathu" written by Vayalar Ramavarma, composed by Devarajan, sung by P. Susheela and M.G. Radhakrishnan. The song combines extreme romanticism with premonitions of revolution--with reddening sky, the rise of a new Man, and art forged in the mines and streets of everyday life. The refrain "Maattuvin chattangale" is drawn from a well-known exhortation to by Kumaranasan (the great reformist poet and SNDP activist) in his poem "Duravastha"(1922): change your rules for the better, or else they will change you for the worse. There is also another reference to Kumaranasan in the phrase "Fallen Flower"--the title of his famous poem "Veena Poovu" (1907)--and the claim made that a "new song" (of communist materialism) now leads the lower- castes (fallen-flowers) more effectively than the SNDP's spiritualism.

Gopalan and Suman get to know each other better.

Kesavan Nair complains to Paramu Pillai about Gopalan's activities. Paramu Pillai pleads helplessness in the matter, and asks for a loan. Kesavan Nair brusquely tells him that he would have to mortgage his house for the loan.

Paramu Pillai agrees to Kesavan Nair's tough conditions for the loan he requires for getting his house repaired. The cunning landlord and his wily aide Velu lay the groundwork to trap Paramu Pillai in a ruinous transaction.

Sumam tells Minakshi about her love for Gopalan, and the two young women have fun at Velu's expense. Kesavan Nair grows suspicious of Sumam's closeness to the communist Gopalan and his family.

Sumam tells Gopalan that she loves him, but he says he is not free to reciprocate. Meanwhile, Mala believes that Gopalan really "loves" her.

The song "Neela Kadamppin Poovo written by Vayala Ramavarma, composed by Devarajan, sung by Yesudas.

Kesavan Nair and Velu conspire to trap Karamban in a false case of theft. The communist activists decide to fight for Karamban. Gopalan agrees to go to Kesavan Nair's house to warn him against such treacherous acts.

At Kesavan Nair's house, Sumam meets Gopalan and he berates her as a class-enemy. She makes a passionate case about how women suffer as much as peasants and workers under feudalism, and changes Gopalan's heart. Kesavan Nair arrives and has an angry altercation with Gopalan. He then beats up Sumam. Sumam stops Gopalan from attacking her father, and Gopalan leaves after slapping the underling Velu.

Mathew realizes Gopalan's love for Sumam as well as his qualms about loving the class-enemy's daughter. He tells Gopalan that love is a mark of "strength" and urges him to affirm his love for Sumam--so that he would "be able to hold the red flag aloft."

Mala is shocked to realize that Gopalan loves not her but Sumam--the upper-caste "enemy's daughter."

Paramu Pillai is distraught at the realization that Kesavan Nair has cheated him and plans to evict his family from their family home.

The love triangle between Sumam, Gopalan and Mala--in which Mala is at once friend-messenger, party comrade, and pulaya loser.

The song "Ambala Parambile Aaramathile" written by VAyala Ramavarma, composed by Devarajan, sung by Yesudas. A love song replete with conventional upper-caste poetic images, with faint communist suggestions about "red flower" and "new dawn" reminiscent of the DMK cinematic strategy.

Kesavan Nair's underlings come to take away coconuts from Paramu Pillai's palms, but are rebuffed by Kalyani and by communist neighbours. The distraught Paramu Pillai feels happy when Gopalan declares that nobody would be able to harm his father.

Mathew meets Gopalan and Sumam near Mala's hut, and "explains" their relationship to them in social/legal terms on the basis of what Kesavan Nair has done.

Mathew speaks to Mala about her sorrow. He tells her of how he too had lost his beloved to police brutality, and tells her not to interfere in the relationship between Gopalan and Sumam. Mala agrees.

Sumam overhears the plan of Kesavan Nair and other landlords to burn down Karamban's hut. She informs the communist workers who chase away the hirelings who come to commit the crime. Gopalan is assaulted by the goons and lies unconscious at the hospital. Paramu Pillai in enraged and screams that he would kill those who had attacked his son. Mathew urges the communist workers to organize a street demonstration against the atrocity.

The climactic scene is a classic melodramatic agit-prop sequence of communist workers marching through the streets, raising slogans and singing the song "Aikya Munnani" on the Communist-led United Front alliance. This was a standard feature of KPAC plays, designed to enthuse the spectators just before they left the theatre--and it is reported that many spectators actually joined in the sloganeering. These songs were also sung (or their recordings played) at the meetings of the communists.

At the end of the song, Paramu Pillai joins the procession with a grin and holds a flag aloft. In the original play, he happily tells the communist activists "You all made me a Communist!" and is told by his new comrades "Not us but the social circumstances did it." The film version ends with a freeze on Paramu Pillai's exultant smile with a screen-title announcing "YOU MADE ME A COMMUNIST."

To get a sense of how the songs of this film are different from the KPAC's popular songs from the original 1952 play, listen to:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IfDgtWBcKk4 (Marivillin Thenmalare--sung by K.S. George)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yg0746GSQ8A (Vallikudilin Ullirikkum--sung by K.S. George and KPAC Sulochana)

CCK 2

Indiancine.ma requires JavaScript.