Pakeezah (1972)

Director: Kamal Amrohi; Writer: Kamal Amrohi; Producer: Kamal Amrohi; Cinematographer: Josef Wirsching; Editor: D.N. Pai; Cast: Ashok Kumar, Meena Kumari, Raaj Kumar, Veena, D.K. Sapru, Kamal Kapoor, Vijaya Laxmi, Jagdish Kanwal, Nadira, Pratima Devi, Altaf, Praveen Paul, Lotan, Chanda, Meenakshi, Chandra Mohan, Zebunissa, Sarita Devi, M.K. Mishra, Begum Bai, Jagdish Bhalla, Rafiya Sultana, S. Nazir, Heena Kausar, Rafiqah Banu, Begum Rizvi, Bilquis, Naseem Banu, Reshma, Shabana, Raziyah, Latif, Geetanjali, Ali Majid, Bihari, Aqeel, Geeta Kapoor, Uma Dhawan, Padma Khanna

Duration: 02:26:25; Aspect Ratio: 1.818:1; Hue: 37.059; Saturation: 0.142; Lightness: 0.235; Volume: 0.212; Cuts per Minute: 7.444; Words per Minute: 24.662

Summary: As shown by the presence of 40s Bombay Talkies cameramen Wirsching and R.D. Mathur as well as the composers Ghulam Mohammed and Naushad, Kumari’s best- known film had been planned by her and her husband Amrohi as their most cherished project since 1958, when Amrohi intended to star in it himself. The film started production in 1964. When the star and her director-husband separated, the filming was postponed indefinitely. After some years, during which Kumari suffered from alcoholism, she agreed to complete the film. The plot is a classic courtesan tale set in Muslim Lucknow at the turn of the century. The dancer and courtesan Nargis (Kumari) dreams of escaping her dishonourable life but she is rejected by the family of her husband Shahabuddin (A. Kumar) and dies, in a graveyard, giving birth to a daughter, Sahibjaan. The daughter grows up to become a dancer and a courtesan as well (Kumari again). Sahibjaan’s guardian, Nawabjaan (Veena), prevents Sahibjaan’s father from seeing her or knowing who she is. Later, Sahibjaan falls in love with a mysterious, noble stranger who turns out to be her father’s nephew, Salim (R. Kumar). Salim’s father forbids his ward to marry a courtesan. The film’s climax occurs when Sahibjaan dances at Salim’s arranged wedding where her own father also discovers her identity and claims her as his child. Finally her desires are fulfilled and she marries Salim, leaving her past behind. The film’s main merit, however, resides in its delirious romanticism enhanced by saturated colour cinematography. Includes the all-time Lata Mangeshkar hit songs

Chalte chalte and

Inhe logone ne.

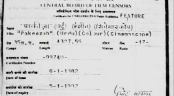

censor certificate

According to Feminist Criticism, most Hollywood films begin with the hero looking at the heroine. And so it is with some amount of surprise that we see several Indian films open with a woman as the ‘bearer of the look.’

Nargis dances with the accompaniment of a musical piece played on

sarangi and

sitar. In this high angle extreme long-shot, she is barely visible behind a gigantic candle in the foreground. Then she emerges, dancing in the

kathak style.

The big warehouse like hall is bare but for the burning and melting candle on the floor and a glittering chandelier hanging from the roof. The dominant colours are the white of her dress and the candle, the yellow of the flames and her jewels.

All this is rendered in one single shot, while the title cards of the film role over the image.

After the title cards, the instrumental piece in

mishra pilu changes to a

taranna in female voice. The shot is still top angle and long-shot, but she is more clearly visible.

The music and the dancing style signal that the beginning of this tale lies in those times when a

tawa’if was known and respected for her art.

There is yet another diversion from the usual mode of Bombay’s popular cinema. The dancer is engrossed, dancing only for herself; her audience sit in the shadows, at the edges of the (cinemascope) frame, situated on either side of the elongated rectangular hall. This

mise en scene has an important implication; she is never seen from the point of view of the men come to see her. Also, they are not individuated as they sit in groups on either side.

Because of the camera angle and because there is nothing seductive and

filmi here, the images produce little voyeuristic pleasure to the film’s audiences.

The shot continues; increasing the distance between the spectators and the spectacle, a resonant male voice introduces her in an unusual way. ‘This is Nargis, sister of Nawabchand.’ So this is a family of famous

tawa’ifs.

The narrator then comments on the excellence of Nargis’ singing and dancing. Her voice and the sounds of her

ghungru-bells drive men crazy. But with little regards for anything else, she dances on.

Once, singing-dancing women held important place in India’s scene of high culture. They commanded respect from clients and audiences, had considerable property, travelled all over the land performing in courts and parlours.

Nargis’ golden hair colour might have been used to distinguish her from daughter Sahibjan. But this also signals at the fact that, once women came from all parts of the world in order to become dancers,

tawa’ifs (and prostitutes) in India.

The word

tawa’if comes from the root

tauf which means to roam around, travel and circumambulate (in Mecca, for example). These were itinerant bands of women performers. Gradually, they became important in royal courts, friends of monarchs, political agents; after retirement some became governesses of young royals. Their condition declined at the time of the British; the latter never understood their fame and considered them as prostitutes. The British annexed their wealth and punished them for their role in plotting the overthrow of the Raj.

The audiences of the film, as well as those who write on it seem to suffer from the colonial mindset. Most synopses inform the film is about a ‘prostitute.’ They also ignore this beginning and the woman who kick-starts the narrative, saying the film is about Sahibjan or Pakeezah.

The latter word, meaning

born-of-purity is a name Salim bestowed on Sahibjan. But film title could be seen as allegorical, and embrace both mother and daughter—or even all the powerful admirable women shown in the film, like Nawabchand (Veena), and Goharjan (Nadira).

The shot continues: Throughout a closed door was visible in the depth of field. It opens to let in Shahabuddin; Nargis approaches him with her arms outstretched. So importantly, we see the man from the point of view of the woman.

So this film begins with a woman, who is the ‘bearer of the look.’

The narrator announces she desires him to take her out of this hell. He promises he would do so; he will not allow her to melt away like a candle.

The night of the observation of the promise arrives and Shahab comes with a horse carriage to the

tawa’ifs’ house to take away Sahibjan, who emerges in a white dress. The voice over continues a little into the next shot of the lonely road in the night and the carriage with the couple.

When they arrive in Shahab’s family house Pakeezah is in bridal red. But the old man screams out is objection, that a ‘woman of the bazaar’ cannot be a daughter-in-law in his house; and the son seems to be petrified before his father’s wrath, incapable of any action. (It should be mentioned here that every time the word ‘tawa’if’ is used, the subtitles in the Shemaroo DVD translate the word as ‘prostitute.’ I have not checked the other DVD's available in the market).

Unlike many popular films, Sahibjan does not fall at the feet of the patriarch but instead runs into the night, hails a palanquin and goes to a cemetery (does not return to her house either).

She lives in the cemetery. Shahabuddin looks for her in the house of all the singing-dancing girls in Delhi.

So, if the man was not the bearer of the look initially, in this scene an extreme close up of his eyes are shown. But even here, he is not the quintessential popular cinema hero. He is not looking at anybody; it is an 'empty look'.

Thus ten months pass. One day, a woman taking care of the cemetery comes to Nawabchand to sell a thick gold bangle (in Bengali style

bala, with two elephant-heads at the joint. Lucknow-Avadh had much cultural and business transaction with Bengal). She recognizes it as one of the pair of which she wears the other; the two sisters each wore one of the pair.

Thus the latter gets to know the whereabouts of Nargis. But she arrives only to find Nargis lying dead, with her daughter by her.

Nawabchand has her sister buried. She mourns not only her death but the fact that Nargis had passed her last days and months in vast loneliness. The woman attendant packs Nargis’ meagre belongings—mostly books—and picks up the infant, who is to be now brought up by the aunt. The latter asks the poor woman to sell the contents of the little trunk and thus Nargis’s books arrive at another part of the city, in the shop of a man selling old books.

A teacher buys one of them and finds a letter Sahibjan had written to Shahabuddin but had no time to send. The teacher tells the shopkeeper, he would do a good deed if he is able to reach the letter to the addressee.

With this coincidence begins the melodramatic content of the film. Shahabuddin receives the letter and learns of his daughter. He goes to meet Nawabchand with the intension of taking his daughter away from her. She mocks at him saying, ‘So the girl too should end up in a cemetery!’ Admittedly she cannot stop a father take up his daughter’s responsibility; but Sahibjan cannot come just yet, since she is about to begin her

mujra. Seventeen years have passed; the respectable man’s daughter has grown up as a

tawa’if. He cannot take her away in front of everyone and cause a scandal; he should return early next morning. As if, his middle-class morality comes to the fore and he turns away.

In a long shot we see the spacious portico in front of Nawabchand’s house where all dramas take place. Sahibjan stands with her back to the camera, while in the background Shahab’s carriage drives away. And then she turns to face the camera in a mid-shot.

In this her opening sequence, she is in bridal red. The film was shot in two phases—once when Meena Kumari was young and once during her prolonged illness. In this scene, made in the first phase, she is breathlessly youthful and beautiful.

The song is one of audacity and a challenge to a chauvinistic male world. ‘These people have taken away my

dupatta.’ Her look and gesture is one of total seduction—as she directs her look, extends a hand or thrusts a lacquered (

alta) foot at another of the men come to attend this musical session.

It is about a woman’s shame that is turned into a force directed against the class driven society—that knows no class, when it comes to oppress and harass a woman. Following a folk-song idiom, the singer in the song, implicates men of different professions:the cloth-merchant who gave one gold-coin (ashrafi) worth of cloth; the dyer who dyed the cloth in rose-red hue; and the soldier, who ripped out the

dupatta from her person. Men dress a woman and men remove the same from her person (then call it ‘shame.’ We assume the song is composed by a woman, who tells her lover, repeatedly, to believe in her at the hour of her shame. Before each verse, she says, ‘O my friend, if you do not take my words for it (if you do not believe me, then ask the cloth-merchant (or the dyer or the soldier).’ Interestingly, the word for the lover-friend is

saiyaan, a derivative of the Sanskrit

sajjan, meaning a good-person.

Those who have come to listen to her are ‘good people’ in the eyes of the society. Earlier a body-builder (

pehelwan), clearly a local goon, had tried to join in and Nawabchand had shooed him away. Only those with money are deemed ‘good’ enough to sit in the

mehfil.

Song:

Inhi logon ne le liya dupatta mera

The men are seated around the portico. She accosts each during her dance and they eye her covetously. Humourless and graceless, they are also baffled, as if, by her insouciance.

At times Sahibjan smiles in appreciation of how she has an upper-hand in this situation. At times, she looks so innocent as if only aware of her craft and not of the circumstances in which it is being produced. But clearly she is not really out to seduce anyone; she favours no one here.

If the mother was not submitted to the voyeuristic gaze, the daughter must negotiate with the entire gamut—from the male gaze, to the male desire to sexually possess the woman. But then we do not see her from anyone’s direct viewing position. There is no shot/counter-shot editing between Sahibjan and the men.

Instead there is one camera position seeing her in full frontal; that position is not taken or created by any character in the film—it is one that evokes the spectator-position.

So by implication each member of the film audience is a voyeur.

The camera cranes up; Sahibjan goes out of frame. The camera reveals several other girls dancing in other rooms and balconies. So, the film goes from the particular to make a generalised statement - but the film will continue with just one story.

The next morning Shahab returns but finds the house locked. Nawabjan has taken Sahibjan away from Delhi to go to her relations in Lucknow (he does not get to know that).

Nawabjan and Sahibjan are travelling in first class (those days these were independent bogies with two lower beds and at times two upper berths as well). In some station on the way, both are fast asleep when in order not to miss the train Salim enters their compartment and sees the sleeping forms. He drinks some water and sits down to nurse a hurt leg. And then he sees the woman next to him (Sahibjan). And then she turns in her sleep and her lacquered bejewelled foot comes and begins to touch his leg with the rocking of the train—in a mise en scene of limbs.

She has been reading Ghalib’s poetry; he smiles and takes a colourful feather from between its pages and closes the book.

The next morning on waking Sahibjan finds a note tucked into her toes bearing a message (so popular amongst Indian film buffs). He asks forgiveness for having got accidentally into the compartment. But then he saw her beautiful delicate foot. He requests her not to place it/them on the ground lest they get dirty.

The irony lies in the fact that she is a dancer; so not only is it her business to place them on the ground, she must also strike the ground forcefully. There is nothing ‘delicate’ about her feet, though certainly they are well cared for and beautiful, also well-formed, because of the severe training that has gone into her dance.

But this message from a stranger fires her with many desires. As Philip Lutgendorf has pointed out in his website of Hindi films Philip’sfil-um (Iowa University), the train is stopped at a fictitious station conveniently called Suhag Pur or the ‘city of happy marriage.’ Sahibjan is filled with the middle-class desire for marriage and ‘respectability.’ We could not say that ‘because’ the situation of the

tawa’if is deteriorating the woman desires the safety of marriage. A film, after all, is as much about when it is made as about the time represented. Since the time of the British and in the decades after the independence of the country, singing-dancing women did indeed sought respectability in marriage—the

bai (barring a few) was obliged to turn into

begum even if she wanted to sing in the All India Radio). And then again, the film is meant for members of the contemporary audience who believed implicitly in marriages; and then ‘tawa’if’ for most (as even till day) means ‘prostitute,’ whose desire for marriage is the stuff so many melodramas are made of.

On reaching Lucknow, Nawabjan wants to live in a private house and not be part of any

kotha or house-of-

tawa’if or be in a locality, where most courtesans are clustered. So she buys off the house of Gauhar Jaan, one of Lucknow’s most famous and powerful courtesans, fallen into hard times now. In order to keep Sahibjan in some sort of anonymity and away from her father, she is to now go as Gauhar Jaan's ward.

This house called

gulabi-mahal or the Pink Palace that includes gardens, fountains and pavilions are set up; some cousins from Delhi and other girls of Lucknow have made it lively.

But this section of the film does not begin with a song-dance sequence; that is reserved for after the arrival of the ‘evil one’ in the guise of a Nawab. That they too are suffering due to the colonial rule and the Privy Purse Act is signalled by the fact he is slightly lamed. A lame man also usually signify sexual dysfunction; but he is going to later crave to sexually possess Sahibjan and so perhaps his lameness is only a sign of his emasculated state in the British Raj. Another piece of history is also hinted at soon after, at the representation of Sahibjan’s first

mujra in Lucknow.

The Nawab sees Sahibjan one day when she rides in an open carriage with Goharjan. He is smitten and comes for her performance in the pavilion in the Gulab-mahal premises.

Gauhar is seated offering

paan to every guest. But when the Nawab is offered one, he declines saying he does not eat them. This refusal of

paan, a very common sexual symbol (attached to a performance by courtesans and common prostitutes) is strange; together with his pronounced limp, the suggestion here would be: he is impotent or incapable of copulation.

Meena Kumari makes a splendid entry in a green dress. She seems younger and lovelier in this scene (was this shot the earliest?). She sweeps her eyes at the assembly; her lips curl little in very small smiles of derision and the she glances away. But she stops a while taking in the Nawab and his seductive gaze and then sits down. All this is subtly rendered.

Soon joins in a man, clearly very different from all the others already present. Gauhar addresses him as

thekedar; so the man is a contractor. And so he is a

nouveau riche (in particular if all this is taking place in the late colonial period, this would also be the war years and so the time of black money and quick gain. Declining to take a seat along with the others on the rug, the man sits near the steps.

She begins her dance with the accompaniment of a song

thade rahiyo o banke yaar. Pandit Birju Maharaj had once told me, during a private conversation, this song was drawn from a

bandish composed by his maternal grandfather Bindadin Maharaj; it ran as

thade rahiyo o banke shyam. This is also because some of the dances in this film are composed by Lachchu Maharaj. Yogini Gandhi (a student of Birju Maharaj) informs she has heard this from Shobha Gurtu, who told her it has been sung in slightly varying

raga structures of

mishra gada and

khamaanj.

Sahibjan asks her lover, who she has not yet seen, to wait as she decks up in sixteen sorts of adornments and ornamentation (

sola shringar). This is a confident woman who knows ‘he’ will wait. There are many men at her feet; but she asks someone else to ‘wait.

The men are all

rasikas—they understand and appreciate Indian classical music and dance. But her song beckoning a lover also arouse in them desire and lust.

Song:

Chandni raat badi der ke baad aayi hai...

Thaade rahiyo o baake yaar

चाँदनी रात बड़ी देर के बाद आई है

ये मुलाक़ात बड़ी देर के बाद आई है

As she describes how she would do her

sringaar one by one, she goes close to the Nawab; he presents her with a bag filled with (gold) coins.

Once again when she approaches him, some rich man — who surely was favoured up till now—throws a bad of gold before the Nawab can give her anything. And the unnamed man, gets up and leaves. Sahibjan reacts, stops singing but continues as prompted by Gauharjan.

It is interesting that Sahibjan is shown as fully aware of her rich client and how she should please them.

Once again she approaches the Nawab, he offers now the second bag of gold. She moves away as if unaware of his move; he is startled but accepts it as a sign that she is not to be disturbed during her recital.

Lastly the

thekedar slides across the floor his 'sign of appreciation; he has joined in the ‘race’ for the ownership of art with money. The Nawab reacts sharply pulls out his revolver and shoots at his hand so the money scatters on the floor. The wounded

thekedar leaves without protest.. Everyone is startled and Sahibjan stops performing.

The film is made at a time when people with ‘traditional money’ looked down on quickly earned ‘new money.’ Naushad had come in later in the project to complete the background music and also had composed some of the songs. He had told me since the film was a very big budget film and since director Amrohi had to approach many financiers for money, who did not always understand the project, they were reluctant to part with their money at the same time they would want to partake of the glamour of cinmea. The

thekedar was to represent all those who thought ‘money can buy art.’ It is possible that this man is a contractor or thekedar who has made (or is making) money in the war years—benefitting from the phenomenon of 'black-money.

Those with ‘traditional’ money are supposed to observe social codes of

la politesse (often translated as generosity too).

The next morning the Nawab sends Sahibjan a bird in a golden cage (one of the film’s very obvious ‘symbols’). The obvious is mouthed by one of the girls; she receives a resounding slap for imagining Sahibjan can be thus ‘caged.’

Song:

Chalte chalte

चलते-चलते

यूँही कोई मिल गया था

Song:

Mausam hai aashiqana,

ae dil kahin se unko aise mein dhoondh laanaa

मौसम है आशिक़ाना

ऐ दिल कहीं से उनको ऐसे में ढूँढ लाना

Song:

Chalo dildaar chalo, chand ke paar chalo

Hum hain taiyar chalo

चलो दिलदार चलो चाँद के पार चलो

हम हैं तय्यार चलो

Song:

Aaj hum apne duaon ka asar dekhenge,

Teer-e-nazar dekhenge

आज हम अपनी दुआओं का असर देखेंगे

तीर-ए-नज़र देखेंगे

Indiancine.ma requires JavaScript.