PART II

5. The Moment of Disaggregation

6. The Aesthetic of Mobilization

7. Middle-Class Cinema

8. The Developmental Aesthetic

9. Towards real Subsumption?: Signs of Ideological reform in Two recent Films

Bibliography

_______________________________________________PART II

5. The Moment of Disaggregation

Aaina hamen dekhke hairansa kyun hai?

-Shahryar

Part I developed a general theoretical framework for the study

of popular Hindi cinema through an investigation of the

conditions of possibility of the dominant textual form, the

'social'. We have seen that in the post-independence era a modular

and 'public' textual form rose to dominance, whose ideological

mission was to produce a coherent subject position in a situation

where the democratic revolution had been broached and then

indefinitely suspended. Three mutually-reinforcing factors served

as the conditions of possibility of this textual form: (1) backward

capitalist conditions in the film industry; (2) a transitional state-form

determined by the interests of the dominant coalition, characterized

by the deferral of bourgeois dominance; and (3) the persistence of

pre-capitalist ideologies and the continued authority of traditional

elites.

Against this background I turn in Part II to a conjunctural analysis

of developments in the field of film culture during a brief period of

political and ideological crisis of the Indian state. The attempt here

will be to develop a 'historical construction' of the transformations

in the field and their ideological significance. A historical construction

is not a 'reconstruction' in all its detail, of the events of the period in

question. It is an attempt to understand the historical significance of

a constellation of events by focussing selectively on certain aspects.

The hypothesis constructed and substantiated here can be stated

as follows: a period of intense political upheaval beginning in the

mid-sixties brought into crisis the political form of the national

consensus (represented by the dominant integrationist role of the

Congress party). Since the forces unleashed by this crisis were re-

contained by an authoritarian populist government, only a limited

transformation of the political field occurred. re-organized in a looser,

somewhat disaggregated form, including a more visible though

fragmented opposition, the political system was able to absorb or

marginalize radical challenges through populist mobilization.

Within the ideological sphere, the film industry faced a challenge

to its established aesthetic conventions and mode of production. It

was able to survive the crisis by a strategy of internal segmentation

which enabled it to absorb the challenge of a politically-mobilized

and demanding audience, and at the same time to reduce the threat

of a state-sponsored rival production apparatus. The segmentation

produced three distinct aesthetic formations-the new cinema, the

middle-class cinema and the populist cinema of mobilization.

This chapter will explain and specify the political and institutional

factors behind the pressure for change within the film industry, and

the manner in which segmentation evolved as a solution to the

crisis. The process of segmentation will be discussed in relation to

the theoretical problem of genre formation as a feature of capitalist

culture.

In political history, the period in question roughly coincides with

the first phase of the Indira Gandhi era, from 1966-when after Lal

Bahadur Shastri's death, the Congress Party elected her to take over

as Prime Minister - to the state of Emergency which was in place for

18 months from 1975 to 1977. [1] This period was marked by the

decline and fragmentation of Congress and the beginning of a series

of political challenges from the left and the right to the Congress

managed 'consensual' stalemate between the defenders of traditional

privileges and free-market principles on the one hand, and the forces

agitating for the realization of the new nation's professed democratic

and socialist ideals on the other. According to some political theorists,

the consensual stalemate, which amounted to a negotiated suspension

or retardation of the democratic revolution, required two conditions:

'a low level of popular mobilisation, when the lower orders of the

electorate voted on the advice of superordinant interests of some

kind'; and 'a loose and largely federal political machine in which

negotiation of local support, at local prices, were [sic] left to local

bosses of the Congress' (Kaviraj, EPW 1986: 1699).

Indian politics, according to Kaviraj, was coalitional in two senses.

There was first of all the class coalition, whose significance is

structural, and entails 'long-term constraints'. This structural feature is

threatened but did not undergo any significant transformation during

the Indira Gandhi era. Politics is also coalitional in a second sense,

at the level of 'parties or political formations'. 'Around a central,

disproportionately large party of consensus were arranged much

smaller parties of pressure, which imposed a coalitional logic-on

both government and opposition political groups.' The right and

left factions within the Congress party had more ideological affinities

with opposition parties like the Communists and the Swatantra than

with each other. Thus the Congress itself was a coalition that enforced

a coalitional logic on the functioning of the party system as a whole

(ibid: 1986, 1698). Both these coalitional structures have a bearing

on the ideological question. While the general theoretical framework

elaborated in Part I must be understood by reference to the class

coalition, the historical construction attempted in Part II refers itself

to the local crisis in the mode of political functioning of the coalition.

The crisis in question begins with the unmistakable signs of

popular dissatisfaction in the late sixties, an indication 'that lower

orders of people were becoming less inclined to vote on the basis

of primordial controls' (ibid: 1699). The particular strategies adopted

by the regime (authoritarian populism based on a direct appeal to

the masses over the heads of the intermediate leadership), were

determined by the challenges to the consensus from both left and

right and a recognition of the need to transform the political form of

the consensus. Through the late sixties and early seventies, the

political situation in India remained volatile, with a wide variety of

movements occupying the centre of the political scene. While one

segment of the communist left was making political gains through

participation in the electoral process, another Maoist segment aligned

itself with the rebellious peasantry and rural working class and

appeared to be gaining ground in the countryside. Urban working

class militancy was at its peak in this period, and a combination of

forces led by the ex-socialist Jayaprakash Narayan mounted a strong

offensive against Congress dominance [2].

The crisis can be usefully described as a deep disaggregation of

the socio-political --Structure resulting in the delegitimation of the

consensual ideology of the state. Given the central role of the

Congress in maintaining the political equilibrium up to this point, it

is not surprising that the party became a prominent site of the

unfolding of the crisis. The fragmentation of the Congress, beginning

with the various dissident formations that sprang up in the 1967

elections, at the state and regional level culminated in what was

popularly known as the 'Indicate-Syndicate' split in 1969. The former

group, led by Indira Gandhi and defined by its left-oriented

programme, broke away and quickly marginalized the Syndicate with

a reorganization of the political machine that rendered the existing

modes of political negotiation obsolete overnight. In the Nehru era,

the ability of the Congress to either marginalize or absorb rival political

tendencies had enabled it to produce and maintain the cohesion

effect. Its modular unity reflected the unreconstructed articulation

of a variety of old and new enclaves into a national political network.

The disaggregation of this structure manifested itself in the form of

a serious political crisis with several possible resolutions.

This crisis represented the culmination of a democratic ferment

which promised a transformation of the social order. During British

rule the nationalist movement had mobilized the masses with the

promise of democracy. After independence, the people were repaid

in the heavily devalued currency of citizenship, whose only tangible

benefit was universal adult suffrage. The new regime found that the

long process of colonial exploitation had left the economy too weak,

that the infrastructure for self-reliant industrial growth had to be

built almost from scratch. In view of this constraint on capitalist

growth, the Nehru era, with its programme of state-led economic

growth and 'gradual revolution' found itself relying upon the

continued operation of the ideology of the despotic colonial state

and the feudal order it had instituted.

The forces opposed to this order gathered strength in the post

Nehru era. Thus, this eventful period represents a revolutionary

upsurge whose potential was hijacked by the Indira Gandhi government

and channelled into an authoritarian interregnum.

'Social Tax' Versus State Competition

The crisis in the ideological instance of popular cinema took the

form of a segmentation of audiences, the obsolescence of. the feudal

family romance, the pressure to develop new textual forms. It was

the period in which the 'social', whose cultural status was remarkably

similar to that of the Congress on the political plane, underwent a

multi-faceted transformation. While one significant causal factor

behind this drive for transformation was the politicization and

mobilization of the masses, another was the state-sponsored

movement that sought to give substance to the idea of a national

cinema. These two factors were related, because the decisive step

towards a new approach to film financing by the Film Finance

Corporation (FFC) in 1969 was made possible by the Indira Gandhi

government's interventionist policies. These were strongly stated by

her and the information and broadcasting ministers in her cabinet,

Nandini Satpathy and I.K. Gujral. The latter, in the course of an

exhortatory speech, told the industry that its demand for a reduction

in entertainment tax would be considered seriously if it was willing

to pay a 'social tax' instead. [3] Thus, government co-operation in

developing the capital base of the industry was to be purchased by

a commitment by the industry to the production of films with

progressive themes, to provide cultural support for the developmental

goals of the 'socialist' government. The industry'S leaders were

habituated to making pledges of loyalty to the policies of the ruling

party, but on this call for commitment unanimity was out of the

question. The maintenance of a posture of deference towards the

leadership was all that the industry could manage. [4] The most that

such government pressures on the mainstream industry achieved

was to inspire some producers to include, within a formally unaltered

framework, 'progressive' elements which they hoped would win

government approval. [5] Sometimes this led to the granting of

entertainment tax cuts or exemptions.

However, the Film Institute and the Film Finance Corporation

together formed part of very different kind of intervention which

was to have a lasting impact. While the institute offered training in

the technical as well as performance aspects of film-making, the

corporation, after a few years of lethargic and unimaginative

functioning, launched a financing policy aimed at the development

of 'good cinema', which for most people associated with the project,

meant a cinema that was realist, narrative-centred, developmental,

and culturally distinctly Indian. Although the change in policy had

been initiated in 1964 by Indira Gandhi when she was the Information

and Broadcasting minister, its decisive implementation roughly

coincided with the arrival of a number of trained directors, actors

and other technicians from the Film Institute.

The FFC had hitherto functioned somewhat like other state

financial institutions, supplementing the budgets of mainstream film

makers (and of individuals with international standing like Satyajit

Ray). Now, changing course to became a producer, the corporation

entered into direct competition with the mainstream industry.

Although the protests were muted in deference to the prevailing

mood of populist mobilization, this development caused great panic

in the industry. The industry had for a long time been demanding

that the FFC should expand its operations by increasing the capital

available for lending, to provide state support for the transformation

of production relations within the existing industry. But it had not

anticipated the form of expansion that the FFC finally chose. While

depriving the industry of even the meagre finance hitherto available,

it now established a parallel industry with an alternative aesthetic

programme. No longer Content to produce newsreels as an

instructional supplement to the entertainment film, the government

was now expanding the sphere of state-sponsored production to

the aesthetic realm. However, the crux of the matter was not the

ideological dangers of state-sponsored cinema (which were minimal

since the FFC policy was administered by an independent body), [6]

so much as the economic danger of the emergence of a formidable

competitor.

The implications of the new FFC policy gradually became clear

with growing signs of audience interest in the promise of novelty,

and Wide support from the press for the experimgntal ventures. The

industry was also preoccupied with the more immediate dangers

foreboded by rumours of an impending nationalization, Gujral's active

pursuit of the Film Council idea, the calculations within the industry

about the mode of accommodation with the government's new

socialist agenda, etc. As president of the Film Federation of India,

Sunderlal Nahata called for internal unity and discipline as the only

way of side-stepping the encroachment by the government which

was seen as the main purpose for the institution of the Film Council.

Unity was to be supplemented with a stance of co-operation in the

national project:

Big social changes are taking place in the country. Society has been

awakened to the: realities and socialistic trends are on in the country

for the welfare of the nation... the government can ill-afford to

ignore our problems when we prove to it that we share in the

responsibilities to contribute to the welfare of the nation in our own

humble way as any other industry does. [7]

But with the visibility achieved by Mrinal Sen's Bhuvan Shome

(1969), which won awards and had a limited but surprising

commercial run, it became clear that a substantial challenge was

gathering strength. In the past, figures like Satyajit Ray had developed

their own individualistic trajectories which precluded any

institutionalized aesthetic programme. The industry had found it

possible to acknowledge Ray as the 'Master' and a national cultural

hero, without jeopardizing its own system of production and values.

As Bikram Singh observed at the time, 'It is mainly the institutional

forces and the strength they began to gain in the late sixties which

the established film industry has found less easy to ignore than it

did Satyajit Ray. [8] While providing opportunities for a variety of

styles and political and aesthetic positions, the new aesthetic

programme was unified by an oppositional stance towards the

commercial cinema. The political dimension of the challenge posed

by this initiative was not lost on the mainstream industry. In a review

of Mrinal Sen's Interview, Screen, while acknowledging its strengths,

called it biased, and nervously observed that the film may appeal to

a 'now growing type of Indians' but not to a 'normal' audience. [9]

Among the many compromises that the mainstream industry explored

as a means of defusing this challenge, one was particularly significant

for the manner in which it sought to blunt the political thrust by

foregrounding the 'artistic' dimension of the new movement.

[[Shome's body learns strange new dialects: Utpal Dutt in Bhuvan Shome

(Mrinal Sen 1969). Courtesy National Film Archive of India, Pune.]]In response to Nandini Satpathy's speech at the National Awards

presentation reiterating the cultural policy of the Indira Gandhi

government, Screen published a long 'critical study' of the speech.

Noting that the speech seemed to be an indication of the policy of

the 'new radical leadership', the writer drew attention to Satpathy's

approving comments on the 'new wave' films. The government was

mistaken in thinking that these films fulfilled the aims of cultural

policy, the writer warned. 'Mrs. Satpathy could be wrong about the

Indian "new wave". Its inspiration appears to be outlandish and

there is little of Indian reality in its products.' [10] By contrast, the

Bombay film 'has been a vehicle of Indian thought, culture and

ideals'. Moreover, the government was warned that by encouraging

the 'new wave' it was playing with fire. The virtues of the Bombay

film lay in their 'innocuous' story-telling technique, while the

'committed film-maker, committed to advance a particular ideology,

can pose a serious danger to society'. On the economic side, the 'new

wave' was a loss-making venture and it was 'unethical', a 'grievous

misconception of priorities' to encourage such indulgence in a poor

country. The article concluded by suggesting that instead of the

new FFC programme, an academy of motion picture arts should be

set up with Satyajit Ray-'the undisputed master of the medium'

at its helm.

The mainstream industry had good reason to invoke the authority

of Ray to serve as an aesthetic focal point that would reduce the

importance of the political dimension. Ray's opinions on the 'new

wave' were first aired in an article 'An Indian New Wave?' published

in Filmfare (8 October 1971) and again in a review article 'Four and

a Quarter', published in Indian Film Culture in 1974. [11] In the first of

these, Ray drew attention to the practical constraints on the ambitions

of the new film-makers. Debunking the trendiness of their enthusiasm,

Ray pointed out that narrative was central to cinema, that 'experiment'

was costly and bound to fail where audiences were untrained in

cinematic language. This criticism was based on the assumption

that experiment necessarily entailed an imitation of 'Godard', a code

word for experimental cinema. Welcoming the new FFC policy, Ray

nevertheless implied that products of such a policy were not going

to succeed with the audience at large. Besides, films like Bhuvan

Shome, which had been hailed as the harbinger of a new movement,

were old-fashioned narrative films after all. In his response the critic

Bikram Singh pointed out that while Ray found foreign experiments

always suited to their time and place, he wanted Indian film-makers

to know in advance the effect of their experiments on the audience,

the commercial viability of the films, etc. The viability criterion

amounted to a pre-emption of experiment. [12] Ray's rejoinder and

Singh's counter-response [13] only reinforced the basic point of

difference. Ray's argument was circular: he regarded narrative as

central; he opposed experiment because it was anti-narrative; he

found that the films made under the FFC aegis were narratives after

all; he therefore questioned its claim to be a 'movement'. It was a

no-win argument. If the new film-makers wanted to be called a

movement they must experiment; if they experimented, they were

out of touch with reality. Mrinal Sen, in a letter purporting to be an

extract from a letter to a friend, summed it up thus: 'to me it (Ray's

article) doesn't mean much except that he emphasizes on the

necessity to build opinion for the "prevention of alleged cruelty to

money-backers". And this, to my mind, hardly builds an aesthetic

case ... [14]

Ray's emphasis on narrative was shared by most people in the

FFC. As the project unfolded, it was narrative that became the most

visible mark of the new cinema's difference from the popular.

However, the dispute between Ray and some in the FFC was over

political and institutional questions. Ray's arguments were anchored

in a notion of the film-maker as an individual artist who must function

in a market that imposes its own rules. He was pragmatic in his

recognition of market constraints but this did not impair his image

as an artistic genius. The new film-makers would introduce a political

element into the aesthetic field, by claiming for their experiments a

significance that went beyond the 'improvement' accomplished by

good narratives. At this juncture, Ray decided to side with the

commercial industry by invoking pragmatic considerations, rather

than serving as a supportive elder figure for the new enthusiasts.

The biggest obstacle to the FFC's project was the strong nexus

between the theatre owners and the financier-distributors, on account

of which the new films found themselves without exhibition outlets.

The construction of theatres by the government was seen as the

only possible solution, but despite such appeals only one or two

feeble attempts were made in this direction. This impasse was one

of the factors that led to compromise formations such as the middle

class cinema, whose most widely known practitioners, Basu Chatterjee

and Hrishikesh Mukherjee, were both associated with the FFC project,

but made most of their films in this period with private finance.

Segmentation

The main sponsors of the middle-class cinema included the N.C. Sippy

family, Tarachand Barjatya, B.R. Chopra, Suresh Jindal, etc., most of

whom were established figures in the mainstream industry. This

cinema was distinguished by its narratives of upper caste, middle

class life with ordinary-looking deglamourized stars. It consolidated

itself by elaborating a negative identity based on'its difference from

the mainstream cinema, thus appropriating one of the main slogans

of the FFC-sponsored 'movement'. An inter-textual reference system

developed thanks to the regular appearance of a set of stars, the

iconography and language of the middle-class household, a constant

use of the popular cinema as a point of counter-identification, even

direct references to other middle-class films (as in Gulzar's Mere

Apne in which a poster and a radio advertisement for Anand figure

prominently). While remaining firmly within the structure of the

established industry, middle-class cinema represented the first serious

and successful attempt at a planned segmentation of the industry

based on the perception of a changed market and the threat of a

rival's potential monopoly over that market. The middle-class cinema

took over that aspect of the FFC's 'realist' aesthetic project Which

consisted in narratives of identification, centred on the urban upper

caste family, a demand for authentic urban middle-class characters

who were recognizably ordinary, etc. The two films which are usually

cited as the first successes of the new FFC policy, Mrinal Sen's Bhuvan

Shome and Basu Chatterji's Sara Akash both presented this aesthetic

of authenticity and simplicity. When it came to commercial exploitation,

however, the main cultural 'resource' proved to be Bengali middle

class culture, which for historical reasons had developed early and

boasted of a rich literary tradition.

Significantly, while FFC failed to create exhibition space for its

films, the middle-class cinema movement within the mainstream

industry was strong enough to prompt a suitable expansion of

exhibition outlets. In many cities new theatres with reduced seating

capacity were built specifically for the middle-class film. The Nartaki-

Sapna complex in Bangalore, which was built in the early 70s,

reproduced architecturally the relations between the mainstream

film industry and its new branch, the middle-class cinema. Nartaki

is an enormous theatre which showed only the biggest of the big

Hindi films at that time. Sapna, which is still associated with the

'realist' cinema, is a single-level theatre wedged into one corner of

the ground floor of the building. Sapna was soon followed (and

elsewhere, preceded) by other such small theatres clinging to bigger

ones. Thus permanent exhibition space was created for a new sector

of the industry.

Certain FFC principles were thus appropriated and developed

into a viable segment of the industry relatively easily due to the fact

that those who had included the middle-class aesthetic principles in

the FFC 'manifesto' were themselves responsible for initiating their

commercial exploitation. Hrishikesh Mukherjee and Basu Chatterjee

were key figures in developing the commercial middle-class cinema

with the financial backing of people like N.C. Sippy. Other principles,

however, seemed doomed to a slow extinction until Shyam Benegal

emerged, literally from nowhere, to exploit their commercial potential.

As editor of Filmfare, B.K. Karanjia provided crucial media support

for all aspects of the new cinema movement. But Mukherjee and

others like B.r. Chopra and even Karanjia, were unapproving of,

and sometimes extremely hostile to the radicals who had used the

opportunity provided by the new FFC policy to make films ranging

from the openly political to the experimental. Such experimentation,

which resulted in films like Mani Kaul's Uski Roti or Kumar Shahani's

Maya Darpan, was ridiculed as an elite preoccupation for which

the masses had neither the time nor the inclination. (Many writers

on Indian cinema spontaneously echo this populist argument, with

the result that the names of Kaul and Shahani have become a

convenient shorthand for the denunciation of experimentation.) A

common sense demand for easy intelligibility was deployed to

mobilize public opinion against experimentation. FN the proponents

of middle-class realism, the role of new cinema was to function as

'leaven' to improve the quality of the mainstream product. [15] Not to

compete with, but to supplement-was the slogan that Karanjia, for

example, developed with vigour in Filmfare. Coupled with the even

more forceful argument of economic viability, this amounted to an

effective prohibition of aesthetic exploration aimed at developing a

cinematic discourse distinct from both the 'realism' of instantaneous

consumability and the aesthetic of the dominant popular cinema.

As a powerful player in the world of the commercial film industry,

B.R. Chopra had much to say on the dangers of the new development.

Chopra had acquired a reputation as an innovator by virtue of having

made successful films without songs (Kanoon, Ittefaq). The latter

was marketed as a turning point in Indian cinema: it was short; it

had taken only a few weeks to complete; it had no songs. Chopra,

who presided over a symposium on 'parallel cinema', leading to a

walk-out by some new film-makers, [16] attacked the very notion of a

parallel cinema movement and heaped abuse on the pretensions of

'a crop of pseudos', who 'in the name of art and realism, (had)

introduced new kinds of vulgarities'. He attribl1.ted the art versus

commerce split to the evil of democracy, which he defined as 'rule

by mediocrity'. Film, 'which was once the entertainment of the

intelligent middle class' had been destroyed by democratic forces

which 'had taken over cinema and converted it into a mediocre art',

leading to a compensatory art film movement. The solution was a

'healthy' cinema that was free from the compulsions of democracy.

The middle-class cinema was thus not only a partial commercialization

of the goals of the FFC project, it was also seen as a protection

against the lures of political cinema.

But it is puzzling that a segment that was manifestly handicapped

by a variety of impediments should cause so much panic in the

industry. One reason for this was the perception that the privilege

of serving as India's 'national cinema' would be more or less

monopolized by the FFC sector. The auteurist FFC films were natural

candidates for awards and for foreign festival entry. Such a turn of

events also presaged government indifference, if not hostility, to the

mainstream industry, which meant that the process of bargaining

with government for concessions, incentives, and other forms of

co-operation could well cease altogether. The industry's claim to

national cultural significance would lack any credibility.

Although there was no possibility of a significant popular success

of the experimental films, their continued production under the

supportive aegis of the government implied real long-term

consequences for the mainstream industry. The alarm would not

have assumed such proportions if it were not for a fear that there

existed a growing interest in precisely the kind of aesthetic shifts

that the political cinema was attempting. While the 'normal' audience

was still there, a 'new type' of audience was perceived as growing.

There was a real possibility that a substantial segment of the audience

for cinema would be drawn to an alternative cultural space, thus

cutting into the size of the middle-class audience for popular cinema.

Although the press and popular opinion continued to propagate the

myth of a cinema exclusively addressed to a mass, proletarian

audience, the middle-class audience (as Ashish Nandy has pointed

out) is the decisive factor for the survival of the industry. The genius

of the middle-class cinema lay in its ability to construct an aesthetic

based on disidentification with the popular cinema while remaining

within the financial and talent structure of the mainstream industry.

But there remained a political excess which the identificatory realism

of the middle-class cinema was unable to accommodate because its

field of representation did not include the domain of the urban

working class or the countryside, where the feudal order was being

challenged by violent uprisings in which urban middle-class youth

were prominent actors. It was through the construction of a

developmental aesthetic that commercial cinema eventually managed

to exploit this political excess.

While the lack of exhibition spaces kept most of the experimental

films off the market, one of the incentives for a commercial exploitation

of urban middle-class political discontent was the exhibition space

that became available with the lapsing of the contract with the Motion

Picture producer's Association of America (MPPAA) for import of

Hollywood films, as pointed out by Shyam Benegal himself (Rizvi

and Amladi 1980: 8). Until this happened, though the 'demand' for a

political cinema did exist, there was no sector in the industry that

was competent enough to exploit it. 'Blaze', an advertising company,

had entered distribution and, sensing the existence of a market for

a cinema different from the popular as well as the 'middle class'

variety, engaged one of its ad-film makers, Shyam Benegal, to direct

Ankur, thus inaugurating the commercial exploitation of the political

dimension of the FFC's aesthetic project.

The politically committed film-makers who benefited from the

new FFC policy had no common aesthetic programme. Some adopted

Brechtian aesthetic principles, while others pursued an aesthetic

based on a critical appropriation of the techniques of melodrama.

Some of the successful films were pure political thrillers in the Costa

Gavras tradition, while a fourth category of films made in the regional

languages, focussed on rural India, with its feudal social order, the

community rituals, etc. This last category provided the material from

which Benegal forged the developmental aesthetic that came to be

celebrated as the political cinema par excellence. This aesthetic was

based on the appropriation of regional realism, and its elaboration

as national cinema, while retaining the regional content as the object

of a strategy of framing that produced a spectator position, allied

with the developmental perspective of the state.

Thus, the FFC's intervention in film production can be read as a

story of the establishment of a research and development facility,

which conducted a variety of experiments from which the commercial

cinema picked up and exploited the most viable forms, leaving the

less viable ones to be pursued by individuals who came to be

identified with aesthetic preoccupations irrelevant to the national

culture. Commercial viability depended on the amenability of the

forms to ideological re-inscription. The cross-over process filtered

out critical experimentation resistant to the prevailing ideologies.

What remained of the FFC's interventionist aesthetic programme

was undercut by the 1975 report of the Committee on Public

Undertakings, which recommended commercial viability as the

primary condition for film-financing.

The Construction of Amitabh Bachchan

While these developments were made possible by a combination of

widespread politicization of cinema audience, especially the middle

class and the students, the declining efficacy of the feudal family

romance prompted a move by the commercial cinema towards an

aesthetic focussed on the mobilization-effect. The legendary star

figure of Amitabh Bachchan, the single most important mass cultural

phenomenon of the seventies and after, with a fame stretching from

the subcontinent to North Africa, was constructed through a series

of contingent occurrences within a relatively short period of two to

three years.

The Bachchan persona, identified with a primordial anger and

populist leadership qualities, was, ironically, given its first exposure

in Hrishikesh Mukherjee's Anand and Namak Haram. In Mukherjee's

films, Bachchan's roles were varied. But beginning with Prakash

Mehra's Zanjeer, a series of films isolated and elaborated the image

of the 'angry man', which soon pushed the other Bachchan persona

out of popular memory. While Mukherjee continued to cast Bachchan

in his films (Abhimaan, Mili, Chupke Chupke, Alaap), the 'industrial

hero' had overtaken the middle-class character.

The disaggregation of the national audience should not be taken

to mean an empirical division of the population into distinct consumer

groups. Although a section of the population clearly patronized only

foreign films and indigenous art films, the rest of the national audience

was not so clearly segmented, and even after the decline of the

feudal family romance, the audiences for the emerging generic

tendencies were not mutually exclusive. However, new expectations

arising out of the political upheavals of the period produced the

conditions for exploration of new forms, narratives and characterological innovations. Disaggregation brought to the fore, class, gender

and generational differences which the social had contained within

its overarching feudal form. Thus, to give just one example, while

the 'social' usually incorporated consumerist references to the latest

fashions and other preoccupations of youthful audiences, these did

not contribute to a distinct 'youth culture' because the paternalism

of the reigning feudal ideology resisted any delinking of youth from

its sphere of authority. But during and after the seventies, commercial

culture gained access to a student/youth audience without paternalist

mediation even if these films ultimately worked towards restoration

of a reformed familial bond. (In Hare Rama Hare Krishna the reform

of parental authority comes after the death of the Janice character

played by Zeenat Aman.) This is a clear sign of an emerging capitalist

tendency towards a disaggregated commercial culture.

In the context of the commercial film industry which was in the

process of a many-sided and unpredictable transformation along

with manifest tendencies to audience segmentation, the Bachchan

phenomenon, though apparently 'in the spirit of the times', is best

understood as a unifying phenomenon which re-established the

popular film industry on a new foundation. While radically different

from the feudal form that had dominated the scene for almost twenty

years, the Bachchan film was nevertheless the means by which the

industry transformed itself internally, providing it with a new identity

.:lat was capable of combining the novel aesthetic possibilities opened

up in the period of crisis with fragments of the old form. The mobilization effect was the most significant new element, whose force was

capable of holding together a new form of modular text in which

the old ingredients would reappear but under a new aegis.

In the era of the feudal family romance, the star-image and the

acting role were linked by the prevailing Hindu codes of iconicity.

The roles of aristocratic or upper-caste heroes and heroines were

played by actors carefully chosen for their looks, which had to match

a certain conception of the 'heroic'. This attempt to approximate

upper-caste and aristocratic ideals of physical beauty dates back to

the time of Dadasaheb Phalke, who in one of his writings, outlined

the ideal features of the actors who would play lead roles (Phalke,

Continuum 1988-9: 65-9). Star glamour in such a context was

indistinguishable from the 'innate' glamour or the splendour of the

elite.

With the Bachchan phenomenon, however, we see the emergence

of a new function for the star image. Now it is not just a question of

exceptional physical features. [17] Nor does it follow the Hollywood

tendency, as described by John Ellis (1992), where acting roles and

star-persona exist side by side, with the films serving as instanciations

of a star's image. In this western model, the star's image is built on

the combination of ordinary and extraordinary traits that are

developed in stories published in star magazines. Crucially, a clear

line separates the star from the acting role, although there is a degree

of seepage of star value into the acting role. [18]

The Bachchan persona is different because in it there is a degree

of integration of star-value with narrative that is unprecedented in

the Hindi cinema. What this demonstrates, however, is not the

unfathomable power of the Amitabh mystique as much as the

demands placed upon the star image by a new form of narrative in

which the innate charm of the aristocracy was no longer the obvious

central content of the text. The Bachchan phenomenon cannot be

analysed in isolation from the construction of this new narrative

form, in which the writer duo Salim-Javed played an important role.

With the disintegration of the feudal family romance, the entry of

'ordinary' heroes into the popular film became possible, perhaps

even necessary. Dockworker, mineworker, railway porter, police

officer, small-time crook: these were some of the roles Amitabh

played in his career, roles that were predominantly lower class and

integral to the evolution of the aesthetic of mobilization (discussed

in Chapter 6).

Such ordinariness brought with it a dilemma: the old hero's pre

eminence had derived from the hierarchies of a social order that

were reproduced within the film text. The middle-class film, on the

other hand, adopted a code of ordinariness that excluded both the

divine splendour of the aristocracy and the political passions of the

proletariat to create a circumscribed representational field where

narrative requirements prevailed over the self-valorizing logic of the

star system. But from the mainstream industry's perspective,

ordinariness, in reinforcing the primacy of narrative movement, is a

threat to the old order, in which as we have seen in Part I,

heterogeneous manufacture, predicated on the assembly of pre

existing 'craft' products and congealed values was the prevailing

mode of production. While the political ferment of the Indira Gandhi

era was strong enough to render the old form obsolete and give rise

to pressures for change, it did not bring about a complete

transformation of the aesthetic bases of the industry. The problem

that the industry faced was how to continue to function with the

existing mode of production without the readymade narrative

framework of the feudal family romance. The FFC project's long

term threat was a reorganization of film-production on the basis of

the centrality and autonomy of the production sector. This was the

factor that prompted a search by established industry figures for

compromise solutions involving a workable mix of star and narrative

values. Salim-Javed also identified themselves with this project for

internal reform. But the resolution that imposed itself finally was

g:me which would make this change of direction unnecessary. This

resolution was made possible by the intensification of the value

deriving from the star system through the infusion of political power

into the figure of the star on the model of the populist cinema of

Tamil Nadu. The star became a mobilizer, demonstrating superhuman

qualities and assuming a power that transformed the others who

occupied the same terrain into spectators. As the auratic power of

the represented social order diminished, there was a compensating

increase in the aura of the star as public persona.

The Politics of Genre

Before moving onto a more focussed analysis of films from these

three segments, it would be useful to draw out the implications of

the historical construction attempted here for the question of genre.

Specifically, how is the segmentation of the industry discussed above

related to or different from genre formation?

The question of genre has been a notoriously difficult one for

critics of Indian cinema. Some critics evade the difficulties by simply

identifying the mythological and the social as the principal Indian

genres. Others recognize that generic differentiation in the Hollywood

sense is not evident in Bombay cinema, although in the early studio

era similar distinctions were prevalent. [19] In a recent essay, rashmi

Doraiswamy (1993) acknowledges the difficulties surrounding the

question, but decides to use the 'personality type' as the basis for

making generic distinctions. In Chapter 3, we have seen how incipient

generic distinctions are undermined by the expansive identity of

the 'social'. However, the 'social' has eluded a precise definition,

serving simply as a label for a large quantity of films which resist

more accurate differentiation.

One of the reasons for the relative weakness of generic differentiation in the Hindi cinema could be the prevalence of a particular

mode of production in the industry, as argued in Chapter 2. Besides,

the possibility of cultural production under such circumstances

bespeaks a whole array of other factors, including a distinct political

structure and an ideological impasse. The pulls and pressures of

such a social organization impose certain conditions of possibility,

certain constraints on cultural production and genre formation. At

the same time, the existence and wide circulation of Hollywood

genres gives rise to imitations and fragmentary appropriations by

Hindi film-makers: the dacoit film was combined with elements from

the Hollywood 'western in films like Khotey Sikkay and Sholay and

'horror films' combined mantravadis and white-clad ghost-beauties

from folk narratives with hairy monsters from a western repertoire. [20]

In the midst of such forays, the portmanteau 'social' has remained

the dominant, and during certain periods, the sole genre with a

contemporary signified. The only element that is exclusive to the

social and thus critical to its identification as a genre is its

contemporary reference. Its dominance attests to a certain ideological

imperative that is peculiar to the modernizing Indian state.

With a few exceptions, these socials are usually musicals. The

musical, which is an intermediate form in which cinema's links with

the stage are worked out, and in which pre-and extra-cinematic

skills and languages are put on display, has become a marginal

form in Hollywood, whereas in the Hindi cinema the continuing

dominance of the musical-social is a symptom of the continued

dependence of the cinema on the resources of other cultural forms.

This is not to be read simply as a question of a gradual

technological advancement which will eventually lead us out of a

dependence on music. The problem of what Rajadhyaksha

(Framework, 1987) calls the 'neo-traditionalism' of Indian popular

film culture is a political, not a technological, issue. The social does

not occur as a transitional form marking the non-completion of some

technological journey. Its function, on the other hand, is to resist

genre formation of any kind, particularly of the type constituted by

the segmentation of the contemporary. This ideological function is

imposed on it by the nature of political power in the modernizing

state. The segmentation or disaggregation of the 'social' is prevented

by the very mode of combination of the aesthetic of the signifier

(music, choreographed fights, parallel narrative tracks, etc.) with

that of the signified (or realism, which requires continuity, a serial

track and subordination of music to a narrative function).

In the period of crisis, we encounter a moment when a genre

formation based on political differentiation is forced on the industry

as a solution to the delegitimation of its dominant formal strategies.

Here it is necessary to free ourselves from the spontaneous association

of genre formation with the specific form it has taken in the case of

Hollywood cinema. While differentiation does manifest itself in the

Indian case, it does not follow the Hollywood pattern. The neg

cinema, the middle-class cinema and the reformed social emerge as

three strong generic identities whose necessity derives from the same

political pressures that led to a transformation of the national

consensus from which the Indian state derived its legitimacy.

In the three chapters to follow, I take up each of the three generic

tendencies identified above for discussion, in order to bring to light

their substantive identity, to investigate their strategies of representation

and their ideological projects.

__________________________________________________________[1] In view-of the goals of my project, I make no attempt at providing clear cut-off

points for the 'period'. There can be no exact overlap of political and cultural logics

of periodization. Taken separately, the period of crisis for the film industry could be

said to begin in 1969 with the launching of the new FFC policy. But it is more

difficult to say when the momentum of a new thrust comes to an end. politically,

1969 and 1977 can serve as more stable cut-off points because it was in 1969, with

the split in Congress, that Indira Gandhi's transformation of Indian politics began

and it was in early 1977 that the first phase of her rule came to an end with the lifting

of the emergency and the electoral defeat.

[2] For a detailed description of the political ferment of this period see Francine

Frankel, chapter 9-13, pp. 341-582. See also Biplab Das Gupta (1974), Sumanta

Banerjee (1980), Achin Vanaik (1990)

[3] Filmfare, 4 July 1969, p. 29. Gujral championed the Film Council proposal with

great passion. The progressive role of cinema would only be guaranteed by a well

organized industry communicating with government through 'a single highpowered

authority capable of acting as a guide and mentor, as well as a responsible executive

agency for undertaking worthwhile programmes of establishing professional norms

and a rational code of intersectional relationship' (ibid: 27). In his presidential address

to the seventeenth Filmfare awards assembly in 1970, Gujral expanded on his vision

by arguing that politicians and artists were united by the bond of 'the people'. He

contrasted the regressive tendencies in cinema with the 'genuine national style of

expression' that had been developed in theatre, literature and painting. that the

intervention was conceived as a measure to break the hold of the popular industry

by setting up a rival sector is borne out by his assertion that while Bombay was

merely following foreign models in its 'retarded growth', the question for India was

which cinema would dominate. Offering to 'share power' with the industry, Gujral

asked for a reciprocal abandoning of 'laissez-faire' and greater social responsibility

(Filmfare, 22 May 1970, pp. 29-33).

[4] Even this form of feudal allegiance without specific commitments on policy

came under severe strain in these years of political turmoil. Thus, at a meeting

addressed by the prime minister, I.S. Johar who was at the time the head of a producers'

organization, responded to the prime minister's criticism of the industry (Mrs. Gandhi

is reported to have said: 'We do have an impression that this industry is only interested

in making money'!) by reminding her of the 'obscenity of poverty' (Screen, 2 January

1970, p. 1). This led to an uproar in the industry, with several major figures writing

letters of protest, publicly dissociating themselves from Johar's position and even

writing letters of apology with a promise of good behaviour to the prime minister

(Screen, 9 January 1970, pp. 1,6; 16 January 1970, p. 1).

[5] Some tried easier ways to align themselves with the 'socialist' power. Thus,

Shyam Behl, in his Gold Medal (1970), had sequences shot at the annual Congress

session, and presented a reel containing these scenes to the prime minister (Screen,

20 February 1970, p. 1).

[6] Several prominent members of the FFC board, led by Hrishikesh Mukherjee

and B.K. Karanjia. resigned in 1976 when the Emergency leadership started interfering

in the affairs of the corporation (Filmfare, 11 June 1976, p. 35).

[7] Screen, 14 November 1969, p. 8.

[8] Filmfare, 10 January 1975, p. 26.

[9] Screen, 11 December 1970, p. 19.

[10] Screen, 18 February 1972, p. 4.

[11] Both are now available in Ray's Our Films Their Films, pp. 81-99; 100-7

respectively.

[12] Filmfare, 14 January 1972, pp. 21-3

[13] Filmfare, 25 Fehruary 1972, pp. 51-2, 53.

[14] Filmfare, 24 March 1972, p. 51.

[15] Filmfare, 1 January 1971, p. 31

[16] Screen, 17 January 1975, p. 15.

[17] Amitabh Bachchan's acting ambitions were initially ridiculed by some producers

Who found his face unherolike; Hrishikesh Mukherjee's role in launching Bachchan

is crucial precisely because unmindful of the unattractive physical features, he cast

him in his narrative films and provided a showcase for Bachchan's unorthodox talents.

Bachchan's first role, however, was in K.A. Abbas's Saat Hindustani.

[18] See also, Dyer (1987)

[19] Sudhir Kakar (1980) has observed that there was a caste system of film genres,

the mythological being the Brahmin of them all and the Nadia-style stunt films being

the shudras. This would seem to have given way to the era of the secular sociaI,

incorporating the brahmanism of the mythological as well gs the shudra antics of the

stunt film. It is thus not surprising that in the crisis period under consideratlon, the

decline of the social led to the resurgence of the 'shudra' genres like the stunt film,

with 'shudra' stars (in the sense of being exploited minor stars) like Jyothilakshmi

and Vijayalalitha reviving the Nadia phenomenon. (See G. Karnad (1994) and B.

Gandhy and R. Thomas (1991) for discussions of the Nadia films.) In Hindi cinema.

in the era of the dominance of the social. there was a sub-culture of gladiator films

gnd ·thrillers' featuring stars like Dara Singh gnd Feroze Khan. Sheikh Mukhtar gnd

Ansari. These were shown in cheap theatres frequented by a predominantly Muslim

sub-proletariat. One of the reasons for the tremendous success of the first few Salim

Javed films was the strategic use of motifs from urban Muslim culture and Muslim

folk religion which was 'In invitation to a hitherto marginalized audience. On the

other hand. the 'Brahmin' mythological did not enjoy 'I corresponding resurgence.

This may suggest that the social had effected an irreversible secularization of the

mythological (Kakar, 1989: 25), although the revival of the latter on television in

recent years complicates the picture.

[20] Steve Neale (1980) provides a good introduction to the theoretical significance

of the genre question in film studies. See also Jane Feuer (1982) and the essays in

Grant (1986).

______________________________________________________6. The Aesthetic of Mobilization

The recuperation of the commercial film industry from the

crisis of the Indira Gandhi era required a reconstruction of its

cultural base and a reform of its mode of address. In the

past its composite textual form had been capable of including a

variety of pleasures. The protocols of darsanic spectacle had been

sustained by the deployment of narratives of familial splendour.

With the disaggregation of the socio-political order, however, the

middle class became amenable to the seductions of a new identity

based on disidentification with the 'socialist' programme in the

national project. The dominant textual form's consensus-effect broke

down and a search was launched for new modes and targets of

address.

Amitabh Bachchan's star personality has to be understood in

this context. Bachchan came to be identified with the dominated, a

figure of resistance who appeared to speak for the working classes

and other marginalized groups. "However, the effectivity of the

Bachchan persona must be investigated not only at the level of a

shift to proletarian themes but more importantly, in its function as a

rallying point for the industry as a whole, a magnetic point around

which the industry reconstituted itself. The ingredients of this persona

go beyond the personal 'charisma' of the individual and include

political, aesthetic and institutional values. Bachchan thus became

an 'industrial hero' (Valicha 1988) not only in the sense that he

played working class characters but also because he was the hero of

the industry.

Bachchan's emergence as the main source of value for the industry

was preceded by parallel attempts to achieve autonomy of the

production sector through an emphasis on narrative. [21] Further

developments contributing to this end were the experimentation

with a novel approach to screen writing in which the indivisibility

of the story and dialogue departments was maintained. [22]

Rajesh Khanna was the reigning male star during the years in

which the Bachchan persona was being constructed. Sippy Films,

Shakti Samanta and other commercial film-makers had tried to make

films with an emphasis on narrative. Shakti Samanta's Aradhana,

based on an old Hollywood melodrama, To Each His Own, proved

a tremendous success, with its message of patriotism and a little

boost from the rumoured 'controversy' over Sharmila Tagore's

appearance in a bath-towel. G.P. Sippy's Andaz was also a 'script

film' with a borrowed French narrative. It was successful, but the

brief appearance of Rajesh Khanna in a flashback, singing the

immensely popular 'Zindagi ek safar hai suhana' became the

highpoint of the film, obscuring the somewhat unorthodox plot

involving widow remarriage. Thus, there were signs that commercial

cinema was itself experimenting with a gradual reform of the

dominant textual form that could preserve the star as the industry'S

main source of value while asserting the autonomy of the production

sector with an emphasis on narrative. Other successes of the period

like Bobby, Jawani Diwani, Imtihan, Hare Rama Hare Krishna

addressed the student/youth segment of the audience. Of the star

figures involved in these films, only Zeenat Aman and Rishi Kapoor

developed lasting careers, Dimple Kapadia, who might have had

greater success than any of the others, left the industry to get married.

While many stars succeeded in developing star-images of minor

significance, only Bachchan evolved into a national figure. His role

is thus to be understood trans-textually, as a figure of cohesion in

the industry as a whole.

'Bachchan's star-image was constructed through two different

points of entry. After an initial period in which he failed to secure

any significant acting roles, Bachchan found a hospitable climate in

Hrishikesh Mukherjee's middle-class films where he appeared as a

cultured, concerned doctor (Anand), angry son of an industrialist

(Namak Haram), a singer who rebels against his orthodox father

(Alaap), etc. In this early period he also worked as a hero of the old

style in films like Pyar ki Kahani and Bombay to Goa, while taking

on roles in some low-budget films as well which might well have

led him the way of minor stars like Navin Nischal and Vinod Mehra.

The turning point came with the scripts written by Salim-Javed. Of

these the most significant were Zanjeer (1973), Deewar (1974), and

Sholay (1975). Bachchan came to be associated so strongly with the

latter that his early films, even the successful ones made by Mukherjee,

have been almost forgotten. [23] This is despite the fact that it was

Mukherjee's casting of Bachchan in the 'brooding' roles of Anand

and Namak Haram that disclosed the potential that would be

exploited on a gigantic scale by the commercial industry. [24]

The difference between Mukherjee's films and those that built

up Bachchan as a star persona was that in the former, the star

represented only an infusion of additional value into a narrative

which retained its primacy. (In a film like Abhiman, the conflicting

trajectories of narrative and spectacle were sought to be resolved

through the narrativization of the star figure.) In the Salim-Javed led

project, however, the star remained a semantic excess of the narrative

process, available for future exploitation.

The value deriving from a star persona is part rent and part

profit. From the star's perspective, his/her body is a source of rent,

since its principal quality, charisma, is coded as a possession that

he/she is 'born with', notwithstanding the work that goes into

producing it. From the perspective of the film-makers, the payment

of rent enables the exploitation of this 'ground' in profit-making

ventures. The star's persona thus accumulates within itself attributes

that are specific to various instances of performance, as well as

various value-laden associations deriving from personal history. Thus,

as an example of the latter, we may cite Bachchan's literary and

political affiliations. His father, Harvansh Rai Bachchan, is a well

known Hindi poet and his mother Teji Bachchan, a distinguished

member of the social elite. (Mukherjee's Alaap showed Amitabh

singing one of his father's poems.(see clip)) The Bachchans were also close

friends of the Indira Gandhi family. Amitabh would later enter politics

as a Congress candidate for parliament and remain Rajiv Gandhi's

close ally for many years. These bits of information were stirred into

the star persona by the press.

The persona also absorbed the characteristics of several characters

played by Amitabh in the early part of his career. Anger, self

absorption, rebelliousness, devotion to mother, proletarian identity

were some of the attributes of the roles that came to be absorbed

into the star persona. While the power derived from elite affiliations

served to legitimate the persona for the middle class, the personality

derived from the subaltern roles was the basis for a new mode of

address, which spoke to the proletariat and other marginal sections

and mobilized the spectator behind the star. The rest of this chapter

will be devoted to a discussion of the first three Salim-Javed films,

Zanjeer, Deewar and Sholay. The primary aim will be to identify the

strategies through which these films constructed the mobilized (and

mobilizing) subaltern hero as an agent of national reconciliation

and social reform.

Zanjeer (Prakash Mehra, 1973)

This was one of the first independent successes of the writer-duo

Salim-Javed, whose star status is intimately tied up with the three

films we are concerned with. Employed for a period in the G.P. Sippy

Films Writing Department, where they participated singly or together

in the writing of Andaz (based on A Man and a Woman), and Seeta

aur Geeta (based on Ram Aur Shyam), Salim-Javed struck out on

their own with Nasir Husain's Yadon ki Barat (based on an idea that

Husain had already tried out in Pyar ka Mausam) and Prakash

Mehra's Hath ki Safai and Zanjeer. While all of these films were big

earners, Zanjeer was the film that launched Salim-Javed into stardom.

Bachchan was chosen for the role of Inspector Vijay when Dev

Anand, enjoying a resurgence of popularity after the success of Johny Mera Naam and Hare Rama Hare Krishna, rejected the offer. As

Salim-Javed recollect it, the final form of Zanjeer owed much to

their insistence on strict adherence to a tightly-composed screenplay.

(Prakash Mehra, the producer/director, had wanted to make room

for a plane hijack half-way through the shooting.) Indeed, by their

own reading, it was a novel approach to screen-writing which insisted

on the indivisibility of the 'story' and 'dialogue' departments

(traditionally regarded as separate skills in the industry) that made

their films distinct.

The institutionalization of the subaltern as mobilized subject,

however, was effected through narrative mechanisms to which we

now turn. In Zanjeer, the Bachchan persona came to be identified

with a subaltern anger and an affiliation with the masses symbolized

by an alliance with a figure representing the Muslim minority. The

hero of Zanjeer is an honest police officer who uses extra-legal

methods to bring criminals to justice and in the process antagonizes

his colleagues and incurs the wrath of the criminal underworld.

Tormented by the memory of his parents' assassination by a criminal,

Inspector Vijay (Amitabh Bachchan) has a recurring dream of a

masked figure on horseback (see clip). The image is traced back to a bracelet

worn by the killer. The dream and the hero's inability to understand

it signal his possession by an elemental force which drives him to

act in unorthodox ways but always towards honest ends. In the

course of an investigation, he becomes friendly with a female knife

sharpener (Jaya Bhaduri) whom he rescues from the street after

persuading her to give evidence against some criminals.(see clip) Next he

confronts Sher Khan (Pran), a Pathan who runs a gambling den in a

mohalla notorious for criminal activities. This confrontation has a

symbolic dimension because it pits Vijay, as a representative of the

law against Sher Khan, who is a law unto himself. Agreeing to Sher

Khan's challenge to meet him on his own ground, Vijay goes to his

mohalla after duty. In the ensuing duel neither is able to defeat the

other. Sher Khan, acknowledging his rival's strength, abandons his

illegal activities and pledges to assist Vijay in his fight against crime

and injustice. (see clip)Thereafter, dismissed from the force on a false bribery

charge, Vijay, assisted by Sher Khan and a Christian old man (Om

Prakash) confronts the city's big crime gang, discovers that the gang

boss is his parents' killer(see clip), and has his revenge. The novelty of the

narrative is the combined result of two elements.

1) The revenge of the orphan: The orphan is a figure of marginality,

deprived of the normal familial pleasures by the intrusion of evil.

The orphan's actions are attributed to a force beyond his control,

haunting his dreams and driving him to act in ways that conflict

with the procedural protocols of the law. He lacks the personal

stability that would enable him to function as a normal law-enforcing

agent. He is a loner and a stranger to his colleagues, a narcissistic

personality. His personal need for revenge is not recognized by the

law that he serves. The law draws upon his strength to implement

its will but refuses to loan him any part of its strength so that he may

exact his revenge. This figure exists in a space between the law and

illegality, a figure whose ability to fulfil his role as a citizen is

obstructed by the pathological history of the subject, which demands

a cure that is extra-legal by definition. It represents the unfinished

character of the bourgeois revolution, the failed reconstruction of

the social in accordance with a new philosophy.

At the same time, the figure of the inspector with an unreconciled

history stands for the existence, within the field of the law, of a fund

of transformative will. It heralds the possibility of a reform of law to

make it serve the needs of the dispossessed and the marginalized.

The law displays its humanity by revealing its pathological side: it

too is haunted by unfinished projects of retribution and redistribution.

Through the in-between figure, the law maintains its position of

impersonal power, while allowing a part of itself to respond to the

demands of those who are its victims.

2) The mobilization of the dispossessed: Whether it is a question

of the suspension of the law for the duration of a retributional

narrative or the re-awakening of the law to its unfinished historical

project, the solution has to be backed by the will of the people. In

Zanjeer the hero's mission is aided by a series of 'donors' (to use

V.I. Propp's term somewhat loosely), who stand for different segments

of the dispossessed. There is first of all the female knife-sharpener,

who represents women on the margins of respectable society,

abandoned by the patriarchal network to fend for themselves. Second,

there is Sher Khan, who represents a criminalized but essentially

honest Muslim proletariat. And third, the Christian old man, drinking

to forget his son's death at the hands of the criminals, who comes to

Vijay's aid with information about smuggling operations. These poor/

gendered victims of society and marginalized minorities gift their

combined strength to Vijay, giving his mission a significance beyond

his need for personal revenge. It is through their active involvement

in the mission that Vijay comes to be identified as a hero of the

masses. He acts with their support but also on their behalf, as their

voluntarily chosen representative. Their support endows his personal

mission of revenge with a social purpose.

The Amitabh persona is a 'proletarian hero' who is at the same

time a representative of the state. It is the act of switching sides,

positioning himself on the side of the 'illegal' (but morally upright)

margin, that gives the figure its power.

Deewar (Yash Chopra, 1974)

Vijay (Amitabh Bachchan) listens to a Muslim co-worker explaining the

significance of the number on his badge in Deewar (Yash Chopra 1974).

Courtesy National Film Archive of India, Pune.In Deewar, however, this double identity of the hero is split into

two separate figures, resulting in a powerful drama of epic conflict,

a civil war between state and community. The film begins with a

traumatic childhood event, the humiliation of the father and his

disappearance, and the flight of the mother with two children to the

city to escape the community's insults. The father (Satyen Kappu) is

an upright trade union leader who is forced to sign an agreement

detrimental to the workers' interests when the mine-owners threaten

to destroy his family. Unable to bear the opprobrium, he disappears.(see clip)

The mother and two children go to Bombay and become part of the

unorganized working class, living on the streets. As the children

grow up, a field of conflict is established in which the state/citizen

confronts the community/subject. Inspector Vijay of Zanjeer, who

embodied the combination of citizen and pathological subject, is

split into two separate figures in Deewar. Inspector Ravi (Shashi

Kapoor) and criminal Vijay (Amitabh Bachchan). Educated with the

earnings of both his mother, who works at a construction site, and

his elder brother, who works as a shoeshine, Ravi grows up to be

an exemplary citizen, passing all his exams with high marks and

after a futile search for employment, trains as a police officer.

Meanwhile, Vijay grows up to be a dock worker and defends his

fellow workers against gangsters who take away a part of the workers'

weekly earnings. Picked up by a gang leader (whose rivals run the

extortion racket at the dock), Vijay soon becomes the second in

command. The gang leader Davar (Iftikhar) becomes Vijay's surrogate

father. Meanwhile, Ravi completes his training and is posted in

Bombay, to tackle the smuggling menace. When he realizes what

his brother does for a living, Ravi tries to back out of the case but,

inspired by a visit to the house of a poor schoolmaster, he resolves

to put aside all personal considerations in the fight against injustice.

The mother Sumitra Devi (Nirupa Roy) who loves Vijay more than

Ravi, nevertheless opposes Vijay's criminal activities and goes to

live with Ravi. Vijay, for whom his mother's love was the sole

justification for living, despairs. Meeting Ravi near a bridge where

they had spent their childhood, Vijay reminds his brother of bygone

days and tries to persuade him to take a transfer out of Bombay.

Ravi refuses and steps up the anti-smuggling operations. Vijay is

pursued on the other side by the rival gang. Resolving to marry his

girlfriend Anita (Parveen Babi), a call-girl, and then give himself up,

Vijay sends word to his mother to meet him at the temple. Meanwhile,

Samant (Madan Puri), boss of the rival gang, returns to take his

revenge. He kills Anita as she is getting dressed for the wedding.

Giving up all hopes of a return to normal life, Vijay kills Samant and

his gang members. Ravi, informed about Vijay's killing spree, sets

out to catch him. His mother hands Ravi his gun and wishes him

success in his mission. She then proceeds to the temple to await the

arrival of Vijay. Fatally wounded by Ravi and pursued, Vijay arrives

at the temple and dies in his mother's arms.

The sequence shows Vijay's exclusion from the Oedipal enclosure as brother Ravi (Shashi

Kapoor) occupies the place of the father, beside the mother (Nirupa Roy). The mother goes

along with the phallic imperative, punishing Vijay with her righteous defence of law, but

when alone with Vijay, she is racked by guilt. Courtesy National Film Archive of India, Pune.

(see clip)The narrative is framed by an awards ceremony at which Ravi is

receiving a medal for bravery. In his speech Ravi invokes those who

stand behind the nation's heroes but are never acknowledged in the

official record. He asks his mother to receive the medal on his behalf

The mother, escorted to the dais, receives the medal but is distracted

by a memory. Her gaze, directed at a point outside the frame, prompts

the 'flashback' which tells the entire story. Thus the story of Vijay is

presented as doubly erased, confined to the depths of a mother's

memory, remaining her secret, not to be recounted in the public

space of the awards ceremony. (see clip)The flashback structure codes the

narrative as a mother's memory hidden from public view, evoking a

powerful sense that the film will tell an 'unofficial' history, one which

the audience can share in, although no official record will include

it. It evokes the community of the 'pre-historic', the solidarity of the

mother's world against the world of the father, the Law. It imbues

the tragedy of Vijay with a secrecy, a subterranean quality. The

'flashback' concludes with Vijay's death and we return to the official

assembly where the mother is still standing on the dais and the hall

resounds with applause. The applause, officially intended for the

brave police officer, has now been partially re-allocated to the

rebellious son. The enactment of masochistic fantasy takes place in

the shadow of the triumphal march of the patriarchal order.

Thus the text stages an imaginary and unofficial elevation of the

resistant subject to a place of honour in the community's informal

memory. Sumitra Devi serves as the link between the world of the

citizen, of law and the rule of merit, and that of the poor, the

victimized and the unreconciled. As a 'woman', she is firm in her

submission to the law, she takes Ravi's side and leaves Vijay when

his smuggling activities are disclosed. As a 'mother', she is equally

firm in her love for Vijay, the elder son, the one who has borne the

permanent mark of his father's dishonour(see clip). By thus splitting the woman

into two functions, the film offers the spectator the pleasure of a

secret liaison with the mother as a surrender to the political power

of matriarchy. The martyred rebel has achieved a reunion with the

mother's body suggested not only by the concealment of Vijay's

story in the mother's memory but also by the image of Vijay resting

his head in her lap at the end and asking her to put him to sleep.

Vijay's tragic destiny is ensured by his attempt to place his mother

in the position of the Father, as the authority whose desires he

seeks to fulfil. After joining the gang, Vijay buys a skyscraper as a

gift for his mother, who had worked as a coolie when it 'was being

constructed. This phallic offering, an invitation to occupy the position

of dominance, is rejected by the mother [25] Instead she punishes him

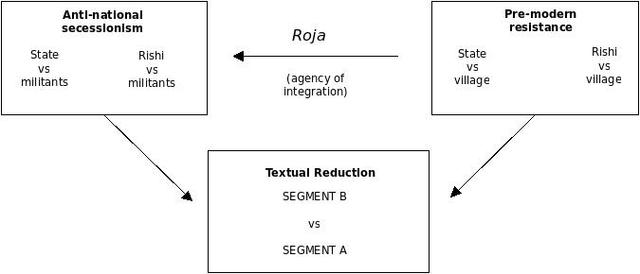

by serving as the vehicle of the Father's law. Before the final